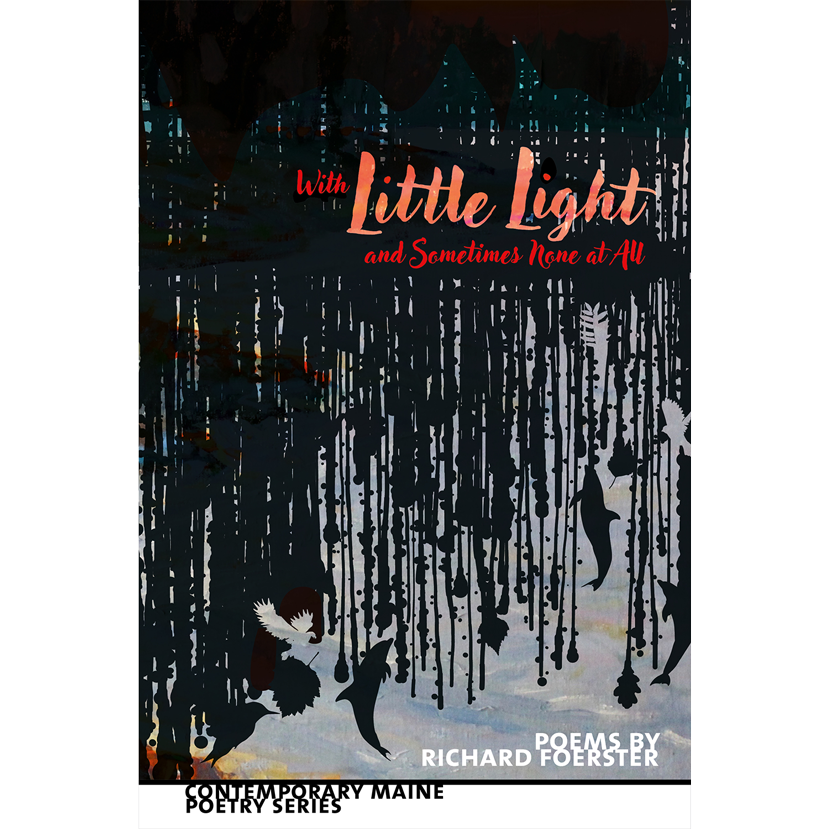

With Little Light and Sometimes None at All

With Little Light and Sometimes None at All, by Richard Foerster.

Littoral Books, 2023,

82 pages, paper, $20,

ISBN: 9798987805725

Starting with the collection’s title, and making inferences from Douglas Taylor’s hauntingly spare and muted cover painting, we can sense that the scene is already set, the light already low. It’s through this darkness that Richard Foerster pulls some of his most arresting, contrasting images, like a poet Caravaggio. As an example, take this excerpt from “Dumbwaiter. Bronx. 1953”: “And I could hear the flywheel spin / in its heaven . . . /. . . as I stretched / on tiptoes to ring the highest / buzzers and announce // the expected calls, and waited / for each tiny door to open / onto a lozenge of light.” These are the kinds of painterly cinematic moments that Forester orchestrates.

A reader might wonder, how does Foerster create these striking reveals? This is hard to put a finger on. But part of the glimmer of the language comes from a carefully measured, almost sculpted diction. Take, for instance, the description of a train in “Bijoux Box” that “gasped in a final fit / of steam, the platform / rose like a wave / that swept me toward / a further judgement / I was ill–prepared to face.” The language manages to be rhythmically percussive, with all its one and two–syllable words, even as it rolls like the wave of steam that sweeps toward the speaker.

Foerster also skillfully depicts the wonders of the animal realm. A friendly bumblebee clamors onto the speaker’s finger while a squadron of cormorants dive, in “On the Afternoon of my 72nd Birthday.” When, at the end of the poem, the speaker shuts his book, we discover the bee is gone. And we miss it. Into its absence, we strain for its presence. But it’s birds that most fly in and out of these poems. A bird corpse, perhaps a crow or pigeon, lies on Portland’s downtown “that weeks of drought / and August sun unfleshed, / here on Free Street, untrodden, / ignored, unswept by wind or lazy / merchants, is perfectly displayed / in the blunt reality of decay.” It’s a disturbing image made even more resonant by all the “un”s layered into the line, as if Foerster is trying to pry us from our comfort in order that we might let our imagination rest on death’s evidence.

In another poem, “At Uluru,” it’s a sparrow that perches on the tip of the speaker’s shoe. “I bobbed my foot. / It would not go. A half hour I pondered that flicking / semaphore, its flare and twitches.” The speaker wonders, at the end of the poem, “Why am I writing this, twenty years on? Oh, envoy / of bewilderment, what is it you have to say?” In both these poems, there’s a sense that the birds, in both life and in death, are trying to tell the poet something, but the poet can’t quite figure out what that message is. Still, he hangs on, wondering, listening, trying to stay in the beauty of bewilderment.

In “I Watched from My Adirondack Chair,” it’s an osprey prowling a lake that steers the poem. The osprey circles “like a mind / circling, then looping back to hover / over some dimly perceptible idea.” The poem opens into an ars poetica for human thought, or more pointedly, a poet’s work, ending with the drenched osprey / poet emerging from the lake, struggling “to reclaim any least gust of air, / too stubborn to let go a lashing burden.” As a poet, I strongly felt this analogy — poets dive for their poems, and the experience isn’t pleasant; it takes a lot out of a body, but it feeds us too.

Minus a bird, this tribute to a life in poetry concludes with the masterful “Ode to My Left Hand,” in which the poet gives thanks to his southpaw appendage, which has begun to tremor, “though I laugh at your seismic / clatter with a teacup on a saucer.” The poem pays loving tribute to “new / mottlings on a sea of inelastic skin.” It’s tender, but quietly powerful, and even thrilling to read. By the end, I could almost hear the roar of a crowd when the poet urges the left hand to “Take up your pen. / It is the tiller.”

— Jefferson Navicky