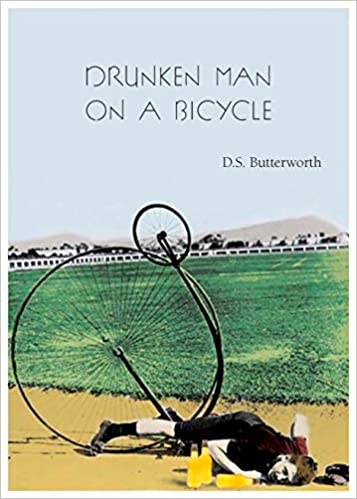

Drunken Man on a Bicycle

Drunken Man on a Bicycle.

by D.S. Butterworth.

Lynx House Press, 2021,

74 pages, paper, $18,

ISBN: 0899241786

The title of D.S. Butterworth’s recent collection establishes a conceit for an unrecognizable America: Drunken Man on a Bicycle. In poems that blur public and private spaces, and sometimes pry them apart again, the absurdity and danger of our social reality outside trace back to something broken inside. Democratic values once assured civic discourse, bolstered national identity. These give way to circus life, which tilts against reason and lifts free from the secure ground of tradition. The careening of wheels passes for communal destiny.

The drunken man on a bicycle tumbles across poems gathering a constellation of imagery, here framing mythic visions of national decline, there pondering the magic of presidential hairdos. There are tonal shifts from the prophetic to the satirical, to the elegiac, to something like lyrical reassurance near the end. But those modes require stable perspectives, moral certainty, and poetic voice can only play at them:

The drunk on the bicycle is America and its king,

is the crowd and ghost of crowd, he is the sleeping

part of the mind . . . (14)

The desire for prophecy — and that poetry might be its vehicle — seems almost able to take itself seriously. But underlying these poems is a persistent lyrical probing that wants to make sense of the irrational.

Butterworth’s poems mine cultural memory for reference points. We seem to be reliving our own Gettysburgs and Alamos, can recognize in our politicians Medicis and Napoleons (“let us number them so we can reassemble the puzzle”). Ghosts of Eliot and Yeats appear and disappear, Shakespeare’s Lear laments: they are all masks that the poet adopts. But the mind of the past feels too remote. Our cultural dysphoria has mythological proportions but not antecedents. This is poetry that wants art to point the way out. But the drunken man on the bicycle is the poet, too.

There are poems and lines that pull the present into focus in striking ways, that defamiliarize the “glean of the inscrutable now.” Democratic values are reborn as rough beasts, “freedom as dark matter.” Our words are now distilled for their “intoxicants.” “[I]nk sluiced off newspapers” becomes “tinctures of anger and confusion.” In these poems, the modernist concern to achieve the adequate symbol confronts an attitude towards language summed up in the verb choice “inking”: verbal manipulations that pull “free from words, free from meaning.”

From this “whirligigging” wreckage emerges recurrent imagery of “animal shapes rich and strange.” Ferret and weasel and “dinner jacket monkey” populate conference rooms. And there again is monkey, “riding the back of a dog godlike,” whose existence is word play, a manipulation of sound.

T.S. Eliot described modern life as a panorama of futility and anarchy. Butterworth names it the “miracle of flying trash.” The miracle contemplated is just how it catches the eye and holds attention. How have we come to “decree[ ] sacred this manner of inebriation”?

Poem after poem highlights the “nation,” an abstraction that becomes conspicuous in its repetition. Sometimes it appears ghostly, like a placeholder, to trace the extinction of what once passed for personal desire and freedom. In the poem “Elegy,” the nation has an unconscious life that seems aware of its shelf life:

Weep, Fool. A nation crumbles from within, the same

way it bloomed, a flower of stone withering under weather

of stomach and spleen. Poor Egg, poor Flower. We fall in

Upon

ourselves and there’s rain. . . .

The mask of Lear is a pose from which to elegize, and elsewhere, Ahab’s quest registers the ambiguity of the nation’s Prometheanism:

. . . sometimes you must kill

the thing you love to make room for your

idea of it, so you can polish it into a rare

sapphire where you can still see, if you really

look, a glimmer of even older ideas like

freedom or justice from behind the glass,

behind the bars. Such beautiful dreams. Meh

The desire to penetrate the mask of alternative facts, to synthesize opposition, to assemble fragments into some visionary whole — these are impulses that shape the collection. And it makes us almost believe in the absurd, resilient idea that poetic language can do all that.

— Christopher Malone