Walking Backwards

Walking Backwards,

Walking Backwards,

by Lee Sharkey,

Tupelo Press, 2016,

89 pages, paper, $16.95,

ISBN: 978-1-936797-90-5

I found a fruitful world, because my ancestors planted it for me. Likewise I am planting for my children. — The Talmud

The poet’s motive for journeying to the past is about the plantings we harvest, the plantings we sow, and the loving life that makes these possible. This is not a genealogical quest, but a stony journey undertaken for wisdom, for tangible signs as to how we may live with each other. Lee has been a midwife of sorts, drawing profoundly compelling poetry from disadvantaged Maine women. She listens to and esteems the poor and the troubled. Lee’s travels to Eastern Europe arose from the same unselfishly observant eye and keen heart. Though forms differ, here is a Primo Levi-like honesty, a capacity beyond romanticization, for recognizing psycho-cultural forces that create folktales and archetypes, bridging present to past, and back again. The eternal question: Can we learn from the past? How to know those once alive as we, as we ourselves will one day become tales and images? How will we, as ancestors, bridge to our children’s children? How will they bridge to us? Lee’s poetry calls to those who share the healing mission of planting for the children.

If I were to research all footnotes, references, allusions and tales (from Walter Benjamin to Beckett to the Torah) embedded in texts and subtexts, a vast range of knowledge would open. Multiple readings are efforts well spent as layers of journeying are revealed each time. Lee is at once teacher and poet of near sublime illumination. Every page is a candle revealing truths, grand and small, in heat and flickers that elude as well as enlighten. At times a densely layered work, it is always evocative, its literal meanings not always apparent. The indelible sense of each poem plants the reader in direct feelings, inchoate yearnings and unflinching observations.

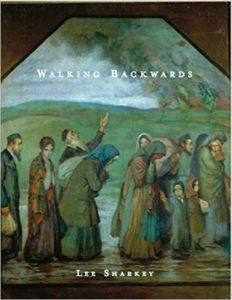

The cover art of Walking Backwards depicts post-pogrom, deported Jews. They walk forward not knowing where they go. Walking backwards, Lee sees where she comes from and backs into a past unknowable until she arrives there. Sad and broken people walk uncertainly, one foot in front of the other. Lee walks one foot behind the other until she joins them in their shared exile and wandering. The poem “In the Capital of a Small Republic,” (which is Vilnius, Lithuania) reveals how very carefully one must tread when walking backwards:

Lowering my right foot cautiously

Lowering my left foot cautiously . . .

The stones are what knowledge I have to go on

Down the seven stinking streets of this plague

The poet bravely engages in an impossible task — reversing time into the past, seeking out moments that might have been undone. Walking Backwards is about communion, reunion, dialogue, a Hasidic tale repairing the torn fabric of the universe, an attempt at restoration of human covenants, an Einsteinian walk along the space-time continuum of history. It is the rare poet who so deftly extracts the historical record into poetic forms. To reach her ancestors, Lee must walk backwards through the Holocaust, backwards to Vilnius, backwards before urban migration, backwards to pogroms and exiles, backwards to medieval wanderings to Jerusalem, backwards to crossings of the Ivrit (the Hebrews) into ancient and modern Israel. Along the continuum, Lee stops at a military checkpoint in the West Bank, where an elder Arab man and a young Israeli soldier both suffer an infernal stasis. She identifies with Palestinian women who wait and hope. Lee’s sad disappointment departs from knee-jerk Israel-bashing, being born of love and better hopes. Can our own fates be altered or undone?

Walking Backwards is a Kabbalah of poetry. Mysteries of histories are hidden between lines. An otherworldliness pervades as poems interact with ghosts and spirits, some of them European Jewish poets Lee has long travelled with — Paul Celan, Nelly Sachs, Abraham Sutzkever (survivors of Hitler’s Final Solution) and Markish Peretz (victim of Stalinist show trials and the Night of the Murdered Poets). Immersed in the poems, one grasps why Lee has sought out these colleagues, their lives radiating the poetry of loss, sorrow and the great longing for life in full bloom. Poetic dialogues may tend to the surreal, one more layer with which to grapple. Lee’s has not been an easy journey, and its telling cannot be easy or immediately comprehensible. Some digging is required for the denser pieces, and with that excavation, the reader is moved, shifted, challenged, befriended. From the poem “Ground Truthing,” we may discern Lee’s path and perhaps a message:

I was bent on knowledge

of the flowering branch the wind that sweeps the sea in its path

It has come to this

rod in hand of one who speaks with scarred mouth

storm on the mountain an arduous god

but this gift each morning

to every one his portion

that opens the matrix the fruit thereof

Lee Sharkey is a poet of love, caring for those who come to her work. The book opens with “Cautionaries,” a series of eight poems advising that what follows is not for the faint of heart, that once living people are “different from paper,” that sorrow, betrayal, shame, severed bonds and death are to be faced. Lee shows us, too, where our work as activist poets may take us. In poem #6, she says:

I slipped into the skirts of Rosa Luxemburg. . . .

Every night we commandeered a print shop;

presses clattered out the great new day.

Even now,

a century later: ink stain on my fingers.

Poem #8 cautions about lost histories, lost names and silence. With Lee, we delve into the fullness of empty places and faces. She warns that the presence of absence is overwhelming:

My friend says she will blow a hole in the silence.

I tell her to look in the mirror

to get the feel of absence.

For the poet and for us, absence is not all that’s found. The earth of our lives must at times be still and empty in its renewal to fruitfulness. Lee Sharkey is planting for the children, all of our children. And I will keep reading because this is as much a manual for living as it is a testament to those whose deaths were too often unnatural. In the final poem, “Something We Might Give,” in conversation with the Vilna poet Sutzkever and with a note from Celan, we are assured that total erasure is impossible, that “A wildflower returns to bloom in the ghetto,” that “Something nests in the chimney,” that “We empty and fill,” that we “borrow books from the unliving.” We are assured that “there remained amid the losses this one thing: language.” Lee’s last lines of the final poem invite us to begin, always to begin:

Among the slaughtered sounds a newborn silence

Genesis words to light the long slumber

— Anna Wrobel