Threnody for Joaquin Pasos & other poems

Threnody for Joaquin Pasos & other poems,

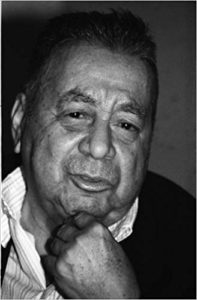

by Carlos Martínez Rivas,

with translations by Roger Hickin,

Cold Hub Press, 2016, paper,

112 pages, $22.50 US, $39.95

NZD, ISBN: 978-0-473-36750-3

One benefit of discovering Cold Hub Press and translator Roger Hickin has been an introduction to Blanca Castellón and Carlos Martínez Rivas, poets whose subject matter is not limited by the exigencies of revolution and political repression commonly found in Latin American poetry. In Hickin’s “Translator’s Note,” to Threnody for Joaquin Pasos & other poems he states that Martínez Riva’s subjects included “love, loss, friendship, mortality, integrity, the visual arts, cats, and alcoholism.”

This explains why Martínez Rivas reminded me of Charles Bukowski, not only because of cats and drinking, but in his alternate tones of celebration and rejection, his impatience with what bio notes refer to as “society’s oppressive orthodoxies and hypocrisies.” In title poem Martínez Rivas celebrates not only Joaquin Pasos but other poets:

Across the centuries they greet each other and we hear

their voices like the distant call and response

of roosters in the night. . . .

In “Please Pay When Served,” Martínez Rivas, like Bukowski, seems to have done some drinking:

I too always

pay when served

that way I’m ready for anything

I swivel my stool one foot on the brass

rail the other on the floor poised in the

shadows in wait for a woman a girl . . .

lose her at last or let her go

find another bar go in sit down

pay as soon as they serve me for

thirty years this has gone on.

While he avoids descending into anguish, Martínez Rivas does retain a certain wariness. In the “The World,” he says:

God made water

the devil poured it in the wine.}

. . .

God made bread

the devil its price. . . .

The table of contents shows that Martínez Rivas is unafraid to take up Big Ideas: “Paradise Regained,” “Entombment,” “Doors of Perception,” “The Masterpiece Project.” Then again he has a poem titled “Cockroaches.”

There are long and short poems (some of the latter appear in this issue). My two favorites are long ones that deal with death and mourning. The title poem “Threnody for Joaquin Pasos” is both lamentation and praise:

And then, we all know the rest: the toll

things took on you. The flood of beings

who approached you, each

with their question

you must answer with a name

that would ring clearly in their ears,

distinct from all others, their own. . . .

While he writes a moving elegy for Pasos, in a different poem he asks another Nicaraguan poet, Francisco Valle, not to write an elegy for Alejandra Pizarnik, an Argentinian poet who committed suicide at 36. “It won’t help her die now. / Or bury her better.” About suicides, he says:

I know a bit about them.

Creatures who ask for silence and are granted only noise.

And it’s those who are closest who are noisiest. . . .

The poem insistently expresses compassion for someone who had always lived a painful life. “What can you say to one who wanted to slip into the silence?” While he offers no direct response to that question, he perhaps leaves us with a plan for defense in a world that’s never been easy on poets. In the title poem he posits this idea:

To make a poem was to plan the perfect crime

To contrive an immaculate lie}

whose purity made it true.

There is another elegiac poem in this volume, “At Home” (subtitled “with my cats and Death”) a short one about his cats who are “oblivious /to the dark cloud lowering /over them: my death.” Despite their regal manner “as they / lord it about the house,” the author frets about what will befall them when he’s gone: “I imagine them /ill and orphaned, prey to bestial / human brutality.”

It’s a tragic world (“Even so, my dear Joaquin, we carry on.”) In “Our Loves,” the final poem, the poet reminds us that while we need those we love:

. . . at the end of life we find we’re tied

by those loves that grew like vines.

We die asphyxiated as these vines entwine

us, crushing our necks, our chests, our loins.

It’s no use regularly cutting them back

with heavy garden shears to try and

stem their inexorable growth.

That would be a lifetime’s work: a task

for Sisyphus or the Danaids, futile. . . .

I think again of the poem about Alexandra Pizarnik. The last line is: “Now if you don’t mind, I’ll call it a day.” It seems a reasonable request.

— Kevin Sweeney