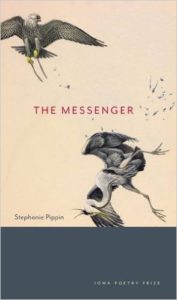

The Messenger

by Stephanie Pippin.

by Stephanie Pippin.

University of Iowa Press, 2013,

70 pages, paper, $18,

ISBN: 978 -1609381646.

Buy the Book

Birds of prey hold a place on the arm of poet Stephanie Pippin’s narrator and especially in her consciousness in her book, The Messenger. In this clarion collection, which was awarded the 2012 Iowa Poetry Prize, Pippin meditates on the liminal boundaries and relationships between the human and the wild.

The narrator’s connection to falcons, vultures, and ravens, as she helps to hatch, heals, tethers, and releases them, is a commingling of awe and need. She is consumed in awaiting their birth, in “Hatch”: “The hours from pip / to hatch, days / to trace the breaks, to see / the shell breached, are agony.” She feels dwarfed by the vastness and vitality of the wild, musing in “Red Pines” that “the egg // is its own law and more real than I, more / alive — a galaxy her wings obey / in everything they do.” She vibrates with awareness of the power dynamics between the winged creature and the human who holds her; in “Summer,” that creature is a messenger of both the wild world and Pippin’s own mortality:

As if to break my wrist,

or will,

she foots the glove —

makes me know

my bones.

Complex powers of life and death play out in “Propagation,” amid

the narrator’s efforts at stewardship, to keep a species alive: “We,

too, are in servitude / to vultures. They hiss / as we back from their nest.

/ They have a future / to protect. It is in my hand — / heavy,

alive, a warm / globe breathing in its shell.” And her ambivalence

finds yet more personal expression in “Raven”:

I am afraid

her trust is temporary, that the world

in which she

cannot live, cannot save herself,

is the world she will want

eventually. And I

the cage that keeps her from it.

Elsewhere, human intervention in the wild is murderous, as in the sequence of poems called “Lone Elk,” which addresses the systematic U.S. military extermination of Missouri elk populations in 1958. In “Live Weight,” a military participant observes: “We keep the heads, the ovaries, the stomachs. We make notes.” In the sequence’s last poem, the narrator addresses the sole surviving elk, acknowledging

the human urge to mythologize nature:

Your existence, inexplicable —

a hellish magnificence,

a message

from the dead. Or just

a lonely animal.

This projection of human meaning into the wild is a recurring notion in these poems. Pippin writes often of a visceral, bemusing empathy she feels for wild creatures, as in “Morning,” in which a songbird is loose in a room:

What I can’t understand is the hold

this has on me: that it will hit and fall

eventually, that after the bird is down, my

mind will confuse its pain with my own.

Elsewhere, nature offers now a spiritual balm, now a welcome respite from it. A stork’s head, suddenly glimpsed, is an “[a]nnunciatory gesture / pale as the angel’s sleight of hand.” But even as she’s moved to lyricize a divinity of wilderness, she is wise to her romanticism. As she remarks in “Iris,” “We’ve all mistaken windowed sky / for heaven.”

Pippin navigates these shifting ways of knowing with absolute clarity and a plain assurance that’s both humble and incantatory. There is power in the candor and ache of her voice, as well as, often, the sudden richness of earthy, fertile music worthy of Seamus Heaney, as in the terrain gorgeously described in “Riverlands”: “open, sogged with

August, / morels swelling like lungs / in the muck.” Her open-form lines and often striking enjambment draw us to slow, hang, and turn amid layers of meaning and feeling. After gutting a doe, Pippin muses,

I find her hollow

shape is the form I want

to sink into.

Life and death are inextricable in these poems, and Pippin mourns

the eventual loss of the bird she once tethered and half held, half

found herself held by. Despite the almost maternal ache of her

grief, she ultimately embraces joy and gratitude for the life she’s

momentarily clutched so close, as in the lovely, airy “Pinion”:

Now that I’ve lived

to see you

vanish, I see

what you mean

is the same

as what you meant

living:

my windfall,

my luck entirely.

Pippin ends the volume with promise and continuance in “Candling Eggs,” in which she embraces the brief, fragile, ambiguous bond of her human body and a wild creature-to-be:

It comes

to this —

warm egg, my palm

made momentary cradle.

Her voice, hailing from such primal borderlands of beings, is itself that of a messenger.

— Megan Grumbling