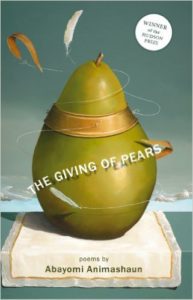

The Giving of Pears

by Abayomi Animashaun,

by Abayomi Animashaun,

Black Lawrence Press, 2010,

82 pages, paper, $14.00,

ISBN: 978-0-9826364-3-5

Buy the Book

The Giving of Pears is an utterly refreshing book of poetry. These delicate and often fanciful pieces are populated by a mélange of ghosts, unborn children, snippets of village life and culture (the author is a Nigerian émigré), and magical tunings. Some of them resemble mystical puzzle boxes, crosses between koans and philosophical conundrums, hearkening back to author Abayomi Animashaun’s study of mathematics. They are clever, sad, amusing and straightforward, without succumbing to pretentiousness. They contain a haunted music and a vigorous imagination, as exemplified here:

I have no words in the machinery of my soul

For how you’ve just pulled me to you.

Released my belt and, now, steadying me

Across the blue flood into the new country.

Divided into six compelling sections, the poems form a colorful travelogue of the psyche, their overriding themes of loss, continuity and hope underscored by an often plain but poignant syntax. In the first section, “Going to School,” Animashaun explores doorways into other worlds, a technique that might quickly become trite; in his hands they have a fresh deftness, as demonstrated in this excerpt from “Tomato”:

Push slowly and enter

A village with its own silent physics.

Its own reddened curvature:

Yellow is the face of the newborn.

Green, the tired hat of the old.

Here sand is red,

And goats lead their shepherd

Through a narrow yard’s edge.

The “Lagos” section acts as hymn, requiem and memoir. The poem “Sunday Mornings at the Barber Shop,” in this section, explores myth, death, superstition and loss through potent imagery entwined with matter-of-fact depictions. This seamless way of braiding the extraordinary with the ordinary is one of Animashaun’s personal hallmarks. Rather than resulting in forced or overly weighted lines, he manages to dance solemnly yet lightly along the edge:

On Sunday mornings

When services begin,

The angels hang their wings,

Abandon their temples,

And come down for a haircut

And nice shave.

“The Unseen” is devoted to ghosts, the unborn, lost loves, and how these beings, whether real or imagined, speak to us, the poetry they engender and the mysterious ways they continue to come and go. “The Other Testament” is an unsettling set of humanistic reinterpretations of religion and figures such as Noah and Mohammed. Animashaun creates an immediacy in these reimagined tales through the use of disjointed phrases, forming a shuffled sense of time in which the present and the ancient become merged. The elegiac musings of “The Tailor and His Strings” form the final section. In “If, In My Next Life,” Animashaun conjures an abstract vision of immortality:

If, in my next life, I have a say

In the molding of clay around

My soul, I’d let my heart be sown

With the sun’s light and traces

From the blue in Cezanne.

Then, geese would find home

In my hands. Birds seeking

Shelter from storms would

Be unafraid to gather and arrange

Twigs on my skull. . . .

The book ends appropriately with an evocation of Rilke, whose imagistic explorations of spirit and time — along with C.P. Cavafy and Kahlil Gibran, and the paintings of Cezanne — guide the poet’s aesthetic journey.

These poems bring to mind Federico Garcia Lorca’s aesthetic of Duende, which often refers to a spirit of evocation, a soulful poetics, an emotional response to music. Christopher Maurer, editor of In Search of Duende, a collection of poems and essays by Lorca, identifies “irrationality, earthiness, a heightened awareness of death, and a dash of the diabolical” as elements crucial to Lorca’s vision of Duende. Such terms also serve to describe Animashaun’s mesmerizing voice.

— Annie Seikonia