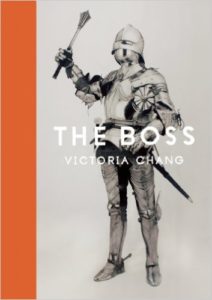

The Boss

by Victoria Chang.

by Victoria Chang.

McSweeney’s Poetry Series, 2013,

64 pages, paper, $16,

ISBN: 978-1-938073-58-8.

Buy the Book

“Her boss is somewhere where is her boss” Victoria Chang asks, flouting grammar, in her new book, The Boss. This past summer, I found one Boss in Pavlov’s Music, in the small Ohio town of Cambridge where I grew up. In the back of Pavlov’s, there’s a selection of used vinyl, which is where I found The Boss — in a dusty copy of his Nebraska that I had a feeling had been sitting in Pavlov’s since the day I’d bought my first guitar almost 20 years ago. As Chang knows, one can find the boss many places — at work, at home, in an Edward Hopper painting, in one’s self, or in Pavlov’s Music in Cambridge, Ohio. Was Bruce Springsteen who Chang meant as her ubiquitous boss? Probably not. However, the spirit feels right. The boss is everywhere.

“The boss is not poetic writing about the boss is not poetic,” Chang says in her poem “The Boss Is Not Poetic,” and that’s for sure. To write about the boss we all have, yet want to be, is to expose our power-hungry, power-deficient, masochistic selves. Definitely not comforting, and The Boss doesn’t leave a reader with a warm, fuzzy, I’ve-been-poured-over-the-landscape-by-poetry feeling. It’s more like the constant fear of checking your email at work one too many times and now the boss is on to you, and you are screwed because the boss don’t play games. Haven’t we all been there? Maybe, but most of us don’t want to think about it so much.

Chang is careful about how she doles out The Boss. Almost every poem is exactly a page; they all meander along the left and right margins and none of the poems have a stitch of punctuation, unless you count capital letters as punctuation, and even those are pretty slim: “can they do that / can she do that yes she can in this land she can.” The result is a rhythmic, blurry and hypnotic syntax that keeps a reader going forward and backward to catch the phrasing. One could find this irritating, but for the most part, I found it pleasing. It wasn’t hard to do, and in fact, because of this syntax, I found myself chanting in my head my own riffs about the boss: the boss is going to the bathroom to bathe in his room the boss is still the boss in the bathroom. . . . I recommend any potential reader to try this. It’s very fun and you’ll be bossing yourself in no time.

So, who is the boss? Who indeed. One boss becomes many. I’m a boss, you a boss, boss, boss me, okay, boss? The poet is a boss with her kids, but is bossed by her boss and, most poignantly, the poet’s father, once a Big Boss in the Business World, suffers a stroke and “when I / ask him the name of his old boss / he says his own name.”

This is a sadly delusional, stroke-impaired moment, but isn’t it true that we all would like to think we’re our own boss? You’re not the boss of me, I’m my own boss! (Insert here: some Ayn Rand/Libertarian/laissez-faire capitalism bullshit.) Well, that’s nice to think, but Chang knows better. You have to serve somebody, and for the most part in this book, the boss is a no-fly zone, the one who sits in the back of the office and points the employees toward the edge of the roof and says: jump, or you’re fired.

And yet, “We are still in awe of the boss and / the law and all the dollars.” The boss is still, and always will be, the boss, whether you find him in Pavlov’s Music (The Boss forever!), or if she haunts you as Victoria Chang’s book did me, bossing me around for days before I resigned myself to the fact that “[t]oday is the boss the boss is today.” I have a review to finish; the boss wants it, and the sooner I accept that, the better. She the boss.

— Jefferson Navicky