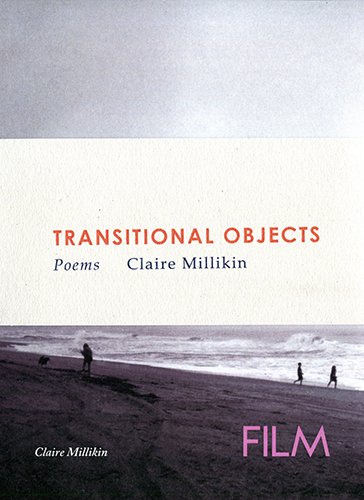

Transitional Objects: Poems

Transitional Objects: Poems

by Claire Millikin, Unicorn Press,

2022, four volumes, 132 pp. total,

paper, $18,

ISBN: 978–0–87775–080–2

Any one of the four 36–page–long booklets that make up Claire Millikin’s Transitional Objects deserves a full–fledged appraisal. Each of the collections, titled Straight Line, Fakes, Film, and Vanishing Point, has its own distinct thematic through line, but there are recurring images that provide connective tissue from one to the next.

In Straight Line, the central motif, if you will, is the mother. She comes and goes, a complex figure, giving and taking away. “On my shoulder my mother’s hand, softly unforgiving, / that’s what I remember of inherited china,” Millikin writes in “Vintage Plates.” In “Carolina Potters” the mother destroys a child’s small animals molded from red earth out of fear they held “magic properties.”

Millikin’s poems are equal parts confident and questioning. They take on reality but will twist and turn to wind up in another place altogether. Take the poem “Straight Line,” which starts with advice — “To manage grief, cut your hair each evening” — and twists and turns to consider the meaning of lies, failing to sell Girl Scout cookies, Jim Crow theaters, and familial inheritance.

A number of poems in Film fittingly relate to movies and photographs — and mirrors. “Blur in Photographs” riffs on what blurring means, “someone moved too fast” or “something unproposed took place.” In the end, “ghost / of blur in images shows a lack of skill, / or more simply hard choices.” Elsewhere, two poems about Polaroids similarly consider the promise and deception of the camera and its offspring.

Some of Milliken’s poems read like stories, accounts of goings–on, family happenings. The opening line of “Whipping Boy,” the first poem in Vanishing Point, leads us into painful history: “When he was a child, my father was whipped. Principally by his father / but also by other boys.” The father in turn threatens to whip his daughter but never follows through, “his way of not hitting me / when he longed to.” The poem ends with the image of “the willows’ switching length.”

A sense of brooding and portent infuses some of the poems in Fakes. In “Selfie as Live Oak Leaves in the Attic,” the poet muses on “too potent memory / that you cannot bear to speak.” The poem “Motel America” considers the way we treat immigrants — “America offers a concrete slab floor” — and concludes: “I’m telling you, this motel / is no place for a child.”

Millikin offers several ekphrastic pieces. In “Barbie Doll as Tutelary Spirit for the Too-Early Dead,” a circa 350 BCE grave stele for a young girl from Sounion, Greece, serves as prompt for a memory of a father’s gift/bribe of the iconic toy woman after church one Sunday. “Showman with Performing Bear in the Westerwald, 1929” uses a photograph by the German photographer August Sander to express empathy for the fate of ursine captives. “The bear—desolate innocent—I cannot stop thinking of its mouth, / how it feels to hold a bit.” The poem brings to mind Thalia Field’s Personhood, which focused on cruelty to animals.

A number of poems open with a startling proposition/revelation. A couple of examples: “In experiments, scientists have learned / that mothers cannot be replaced with wires” (“My Mother’s Letters, After Hart Crane”); “It took a month for people to notice the moon was gone” (“After the Moon”); “Offices should be celibate, but some are not” (“Office Hours”); “All-night grocery stores are almost like oceans” (“All-Night Grocery Stores”); “The stillness of forgery relates to safety” (“Fakes”).

If the promise of these sometimes surreal, always engaging overtures is not always kept—and those are rare instances—they always lead the reader into explorations of place and time. Millikin is brilliant at drawing us into her universe where doors open and close, where family members comfort and deceive, where, to quote the final couplet of “Aperture,” “Dreams are ruins that return, / the backyard a swamp after storm.”

— Carl Little