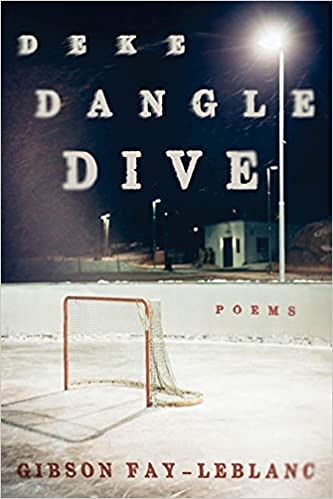

Deke Dangle Dive: Poems

Deke Dangle Dive: Poems

by Gibson Fay–LeBlanc

CavanKerry Press, 2021, paper

94 pages, $18

ISBN: 978–1–933880–86–0

In an act of title foreshadowing, Gibson Fay–LeBlanc reveals a significant thematic thread in his second book of poems: hockey. Deke and dangle are strategic moves by a player to fake out an opponent while a dive is dramatically falling to convince the refs a foul was committed. At the same time, in an extraordinary poetic performance, deke, dangle, and dive characterize the verse’s delivery, its feints and face–offs, as well as the disposition of the author, who, throughout the 40 or so poems, questions his life maneuvers.

Fay–LeBlanc’s self–interrogation begins in the opening poem, “Wing and a Prayer,” a kind of overture. Among other things, he considers his “shallow root system,” a thundering universe, and a dying brother:

I’m supposed to let whatever

happens be what I want

but I still want, I want, I want

my brother’s cells to stop their war

on each other.

More than half the poems include references to hockey, some of them central, some made in passing. The poet accepts his obsession — he loves the game for all of its sometimes brutal elements — and makes of it a medium for considering existence.

“Hockey Poem” takes place in the locker room where literary talk is frowned upon; the players “roar” with laughter when a novel or poem is mentioned. Here and elsewhere, Fay–LeBlanc shares his mistrust of poetry even as he’s setting down his lines and exploring his priorities: “Dear Committees, keep your fucking medals // for reading poems or writing them — someday / I’ll deke that goalie. . . .”

Elsewhere, in “How to Deke,” Fay–LeBlanc might be describing his poetic practice, the “twitch, pivot, push, spring” that marks much of his verse. He is expert at messing with expectations from line to line, pulling off a variety of neat moves, sometimes linguistic, that leave one smiling with admiration, even wonder.

Many of the hockey–related poems involve the author’s brother, Leland Fay, who fights — and succumbs — to cancer. In “Unwritten,” the poet describes a loving brotherhood of shooting pucks and roughhousing, of run–down apartments and nicknames (“even / G–string”). The ending finds the poet on his knees, praying

to all I barely believe, because how else

will there be decades ahead to be brothers

in this poem I don’t write, then don’t write more.

In several poems, Fay–LeBlanc practices a more formal prosody, using full and half rhymes as part of the stitching (he also pulls off a stunning sestina, “Self–Portrait, with Dish–Rag,” using another poet, Emily Hollyday’s end words). “Stay” features three–line stanzas with first and third lines subtly echoing. Here’s a stanza from toward the end where he muses on his shortcomings:

I can’t give my love the river,

a trail, a coal–black wood where we

never walk without the other.

That “love” comes to the forefront in the affecting and apologetic “To My Wife.” After admitting he hasn’t called the plumber yet and the “fridge keeps blinking / its quiet death: 8–8,” the poet highlights their teamwork: “We know how not to fight and how to run a year– / long camp for two good boys // who keep breaking windows in a garage that may never / not be falling down.”

Those two sons are another recurring motif, the poet celebrating their individuality while ruing his inability to protect them. “Early October” describes Halloween with one boy dressed as a “bloody Coca–Cola,” the other, an outlaw with pistol. “I’m the dad who turns / off the third school shooting / this month — police found / five guns on him, still / to be fired” though he realizes his boys know it all, “sure as they know I’ll smile / and don a mask with dark fangs.”

Fay–LeBlanc returns to his kids in “Fields, Roadsides, Throughout,” a multi–part poem that revolves around a run the poet takes to help screw his head on straight. While observing his bucolic surroundings, he reflects on his family, including the “little men” — his boys — who read to each other one minute, claw each other’s eyes out the next.

The poem is dedicated to James Foley, the American journalist who was beheaded by ISIS in 2014. Fay–LeBlanc had met him once and feels his own unworthiness in the face of Foley’s dedication to his job — that he returned to Syria to report even after being imprisoned there. The poet on his run tries to forget the ugly news of the day: “collapsing / skyscraper icebergs, / whale–bleeding sonar, / brick dust left / by extra large / remote control toys / roaming actual skies.”

Which leads to a final observation: Fay–LeBlanc’s kinship with the Wordsworth of “The World Is Too Much with Us.” In the opening lines of “Self–Help” the poet advises, “Resist the urge to start the day / with what other people think,” while in “The Latest in Nanotechnology” he points out the flaws of hand–held devices while saluting words “so old they’re new and known / and felt.”

Deke Dangle Dive is a splendid creation, from the arrangement / order of the poems to their individual brilliance (my copy ended up with post–it notes on nearly every page). Other stand–outs to mention: “At Sea,” “The Varieties of Moss on Deer Isle,” “Mother,” “Words with Friends,” “Low,” and “Going to Church.” The lastnamed merits special attention: a dazzling 22–line invocation of the holy places and objects that surround us.

In the aforementioned “Fields, Roadsides, Throughout,” the poet writes that he’s tired of “poems / puffed, spit shined, / and ultimately / unable to tell / us how to be.” Ultimately, his own poems, so handsomely crafted, tell us how we might exist in an unjust world. There’s consolation there, grace, and beauty.

— Carl Little