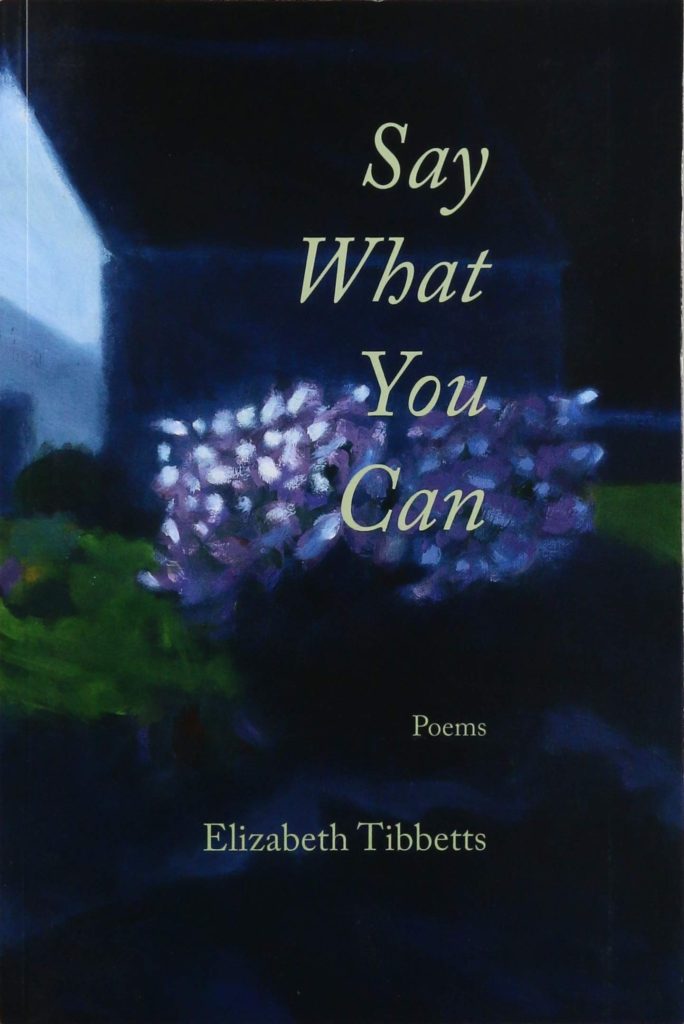

Say What You Can

Say What You Can,

by Elizabeth Tibbetts,

Deerbrook Editions, 2019,

100 pages, paper, $16.95,

ISBN: 978–0–9600293–1–0

In her second collection, Elizabeth Tibbetts from Hope, Maine, offers 70 or so poems marked by empathy and a near pitch–perfect ear for turning a line. Many of the poems were prompted by Tibbetts’s experiences as a wife, mother, grandmother, niece, neighbor and nurse. They are well–crafted, full of music, and abounding with memorable turns of phrase.

The opening poem “The Saint of Returnables” is a loving portrait of a man who bicycles a rural Maine neighborhood, March through November, collecting bottles and cans. Glimpsing his expressionless face from a passing car leads to thoughts of his soul, “where he stores / everything and watches and waits for what’s / to come.” The poem ends with images of spring and resurrection, of “leaves / so fierce they push up green inches every day.”

Tibbetts is fearless in her leaps of imagery. “June World” offers these two stunners: “. . . and the sky, the mood of a cut peach, // casts itself onto the river and mountain / beyond, which basks like a giant’s yellow cat. . . . ” Such surprises compel re–reading, a desire to be startled all over again.

Several poems reference Tibbetts’ role as caregiver. In “Swimming,”

a patient’s question “Do you skinny dip?,” presents a quandary: “Why not say ‘Yes,’ crack the old // professional code (it’s only love that sustains us) / and give, along with his morphine, a glimpse / again of a body swimming unencumbered.” Elsewhere, “Sonnet for a Nurse” is a remarkable reflection on mortality, where words are

Something to soothe us because there’s only

time stretched between me and my own serene

body cooling beneath a stranger’s hands.

And there is humor, be it describing the lovemaking of some turkeys — “The hen wears [the tom] as casually // as a hat” — or slugs going at it: “they hang, heads / down, like flesh esses in slither and caress.” Sometimes the comedy is dark, as when the check and chocolates a father gives for Christmas are accompanied by “a two–week supply // of potassium iodide to stash / in my car in case there’s a nuclear / accident.” This unusual gift makes the speaker wish she could “crawl into the crèche and fragrant straw / with the oxen and sheep.”

Tibbetts is a master of the Maine winter poem. “Six–thirty, Six Below,” “Winter Solstice,” “Details,” “Winter of 2003,” and “Winter Simple” paint cold beautiful northern pictures of life in the chill season. In the last–named piece, the poet finds comfort tucked in bed with a volume of Akhmatova’s poetry and a thick fashion magazine, her vice and sin, where “a pair of shoes snagged me so hard I moaned.”

Several poems find Tibbetts exploring the ekphrastic. In “‘Sea

of Words,’ a Painting by May Stevens,” the poet describes encountering a haunting image by the late artist–activist (1924–2019) that shows women oaring small boats across a surface made from thousands of words. Tibbetts uses the occasion to consider how she might swim face down in this “cursive chop” and to contemplate floating on the waters of birth. The collection also includes three pieces prompted by images by Robert Shetterly, part of a collaboration for the 2012 Belfast Poetry Festival (it’s not the first time the artist’s work has inspired poetry: See William Carpenter’s Speaking Fire at Stones, 1992).

The third and final section of the book takes us to Guatemala via a series of reminiscences of a trip Tibbetts made as a young woman in the 1960s. In the 20 poems, she offers her own “questions of travel” — and in a sense places herself in Elizabeth Bishop’s poetic line, offering us pictures of a Central American country much as Bishop did of Brazil.

The poems are personal and often dark, several of them involving sketchy individuals and scary incidents. And some indict: “El Pulpo” recounts a visit to the former palatial compound of the United Fruit Company, which ravaged the country. There is a boating expedition on the Rio Dulce and a canopy walk. The final poem, “Nothing Lost,” brings her back home. Where in her

southern sojourn she had dreamed of “snakes / uncoiled across the warm road,” now she sleeps in a “carved bed of flowers filled with snow.”

There are many more poems worthy of special notice: “Still Here,” “Song of the Entomologist,” “Among the Chosen,” “Bird Woman,” “Energy,” “Reading Time,” “Lessons,” “Valerian,” and “Gutting,” to name a few. Say What You Can is superb from start to finish, each poem as well–turned as a Brother Thomas vase, as resonant as a favorite song. A keeper to keep close.

— Carl Little