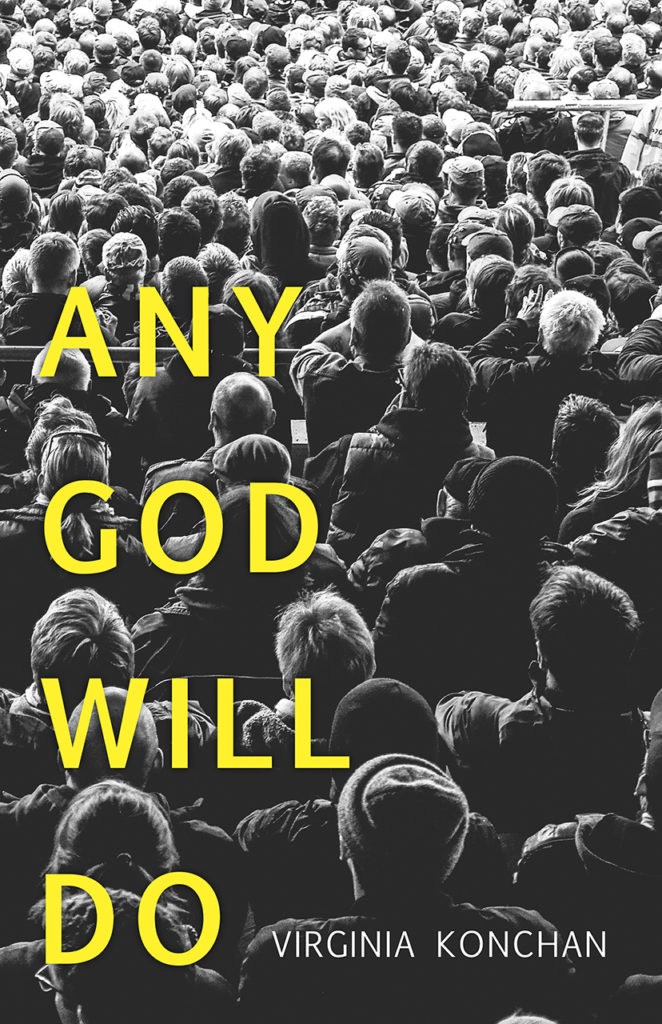

Any God Will Do

Any God Will Do,

by Virginia Konchan,

Carnegie Melon Press, 2020,

80 pages, paper, $15.95,

ISBN: 9780887486531

In Virginia Konchan’s poem “Theory of Everything,” a man “begins to levitate, / the way a painting begs / to emerge from two dimensions, / bruised skin and dappled fruit.” So too the poems in Konchan’s second collection Any God Will Do. The poems strain to jump from the page, and through some kind of poetic magic, they often perform this miracle.

Reading these poems is addictive like watching George Carlin loops continuously on YouTube — you can’t miss the mastery on casual display. And you think this’ll be the last one, but then you say: “Just one more, just one more. . . .” The poems speak effortlessly, so smart, so funny, so witty. In fact, in the collection’s opening poem, “A Star Is Born,” the speaker says, “I confess: / I like witty people. I credit / them with having overcome / the shitiness of the world.” Indeed, I count Konchan among these witty people, and as I write this review at an exceedingly shitty time of the coronavirus world, these poems helped me rise above, at least for a few moments.

There’s a strong uniformity to this book in terms of poem length, style, and even order (the poems are alphabetical!), but I especially felt the coherence with voice. The first–person speaker is very consistent and consistently surprising. At one point, I scrawled in the margins of a poem: “this is a running monologue, or a monologue delivered on the run.” The speaker is a performer, and is aware of her performance. My favorite example of this performativity was in the stunning poem “Aubade,” where the speaker says, “In the end, / happiness and meaning / are irreconcilable differences, / especially on the dance floor. / I am passionate, of course.” It’s that “of course” that is so brilliant. It feels casual, off–the–cuff, but it also signals an awareness of performance, a self–awareness that’s a wink to the reader, as if to say, I can’t help myself !

To that extent, the performance feels utterly authentic, and so when the speaker in “Desideratum” says, “My human desire is simple: / to live on the perpetual cusp / of extremity” the reader is

happy to accompany the speaker to this extreme point, “the hour / between disbelief and ecstasy,” because the speaker is such a

beguiling and entertaining guide. In a way, one gets the sense that the speaker will do almost anything for the sake of the poem, i.e. for the sake of the reader. For example, in “The Golden Arches,” the speaker’s competitive side emerges at the end of the poem: “You call this a sunset? / Do not go anywhere. / I can make my body / into a starfish for you.” That underlying desperation below the humor is what feels so authentic, and leads a reader further into the book’s darker worlds.

In trying to come up with a metaphor for my experience of reading this confoundingly jovial book, this is the best I could do: you’ve found yourself in a sword fight (as one does when metaphors become stretched), and your opponent is dressed in frilly things or perhaps a nice A–line dress. She starts dancing around, doing all kinds of crazy, acrobatic things, and just when you find yourself almost starting to chuckle — zzzzip! She lacerates your cheek and you’re bleeding. Where did that come from? What happened?!

That’s what it feels like to be listening to this witty voice talk about Excel or infomercials or Fucking Facebook, and then before you even know it, her knife hits its mark. The book essentially is about betrayal, or a set of betrayals and lesser disappointments that pile on top of each other until lines like this in “Apocrypha” pop out:

. . . The eighth mystery

of the world is when what is familiar

does not automatically lead to contempt.

Take marriage, for example.

Take the three– and seven–year itch.

Or the utterly devastating ending of the title poem: “Lying to my face, after asking you to swear / to god, any god, is how I will remember you.” “Good God, / our dying changed everything.” And so what is left in place of the betrayed relationship? Loneliness, for one thing, and the beauty of being alone. Three of the more striking poems end this way: “I wake. It is dawn. / As foretold, I am alone.” (“Aubade”); “May you not die alone.” (“Apocrypha”); and an anthem for poets everywhere: “All I ever wanted / was to be fucked and left alone.” (“Adult Entertainment”). This alone–ness isn’t loneliness, but rather one notices a sense of relief, as in a ceasing of performance or the playing of games, whether in love or on the page. And thus,

When happiness comes back,

it comes back on stilts,

on acid, on bended knee.

Like a prodigal. Like a madrigal.

Like a boss man, gold chains glinting

in the harsh September sun.

(from “The Gilded Age”)

All of Konchan’s bling and charms are on display here, and also the whimsy, the drama, the self–deprecation, and the devotion.

I love that happiness is a boss man with gold chains. This may be my own bias showing through, but with this image I pictured a golden–haloed Bruce Springsteen tearing it up on stage. Happiness, like everything else, is a performance, and in Any God Will Do, Virginia Konchan is the kind of performer who is impossible to ignore.

— Jefferson Navicky