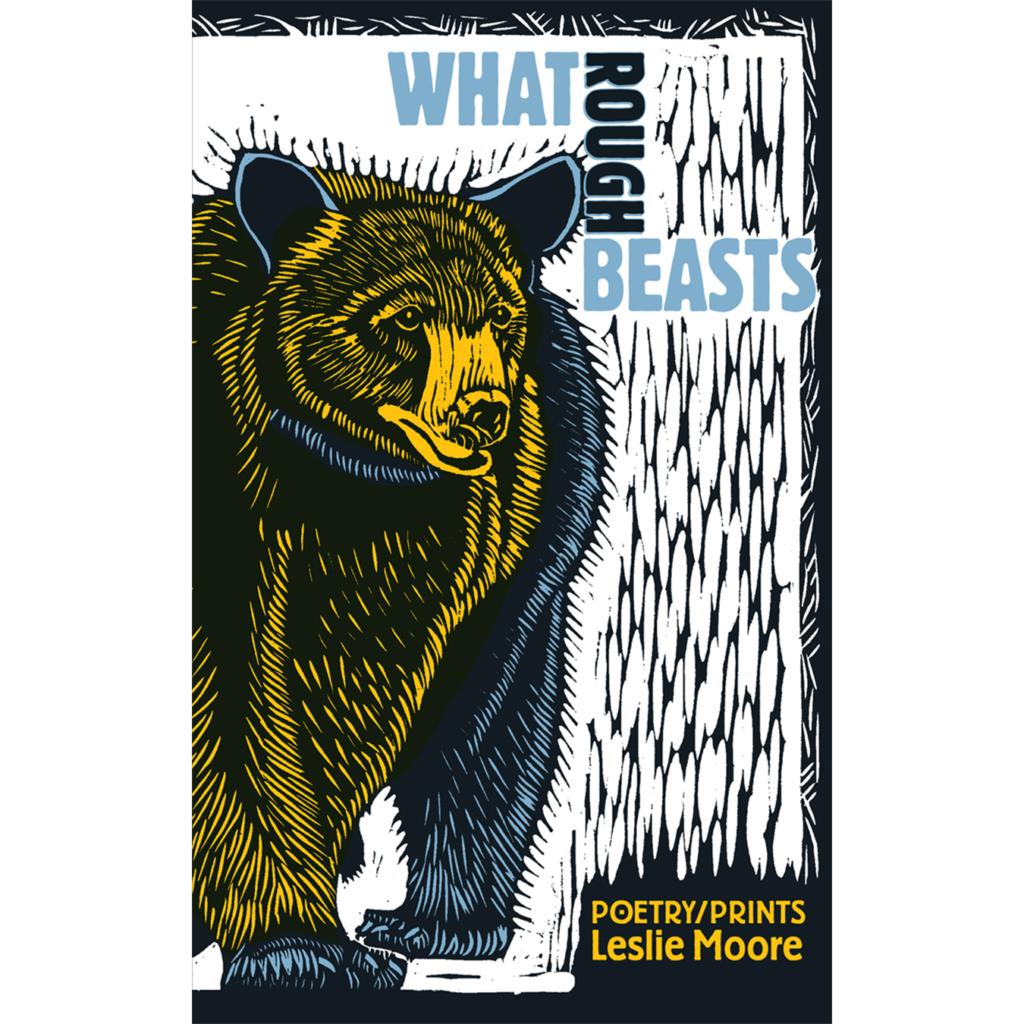

What Rough Beasts: Poetry/Prints

What Rough Beasts: Poetry/Prints

by Leslie Moore.

Littoral Books, 2021,

70 pages, paper, $18.95,

ISBN: 978–1–7357397–4–8

The title of Leslie Moore’s book comes from Yeats’s famous poem “The Second Coming.” It’s a bit misleading: In the context of the Irishman’s verse the three words connote apocalypse, whereas Moore’s creatures are for the most part welcome inhabitants of her Maine world — rough around the edges, perhaps, but beloved, nonetheless.

That said, the title poem, with its evocation of a U.S. president inciting a coup, makes Yeats’s dark vision once more relevant. That insurrection and a red–tailed hawk gyring over the blueberry barrens atop Beech Hill in Camden prompt the poet to state “a hundred years and the center still does not hold.”

The book’s opening section, “Naming Birds,” conjures close encounters of the bird kind. Crows receive the most attention. Moore adds to the rich line of corvid poetry (Ted Hughes, Louise Bogan, et al.) with such poems as “Oracle” and “Riddle of the Crow.” In the first, the bird in Japanese artist Ohara Koson’s print Crow on a Snowy Bough speaks to her, but she only hears it “when I wake from my sleepwalk, / when I pause, / when I become / the caw.” In the second, a local crow nurtured on kibbles is “a black panic in feathers.”

A sense of play and humor marks a number of poems. “Naming Birds” questions the decision to call a “carrot–topped bird / in his herringbone jacket and ashy underpants” the Red–Bellied Woodpecker. Moore suggests an alternative, “Orange–Coiffed Woodpecker,” whose swagger recalls Cyrano de Bergerac: “Both flaunt notable noses / and plenty of panache.”

In the two subsequent sections, “Visitations” and “Totems,” Moore’s menagerie expands to include fox, bear, flying squirrels, a glass eel, garden spiders, frogs, and other animals found in her Belfast neck of the woods. She is inventive in her imagery: tadpoles squirming inside their eggs are “like crazed commas trying to escape the lines of a poem.” And “Animal Tracks in Snow” delineates the various “fine traceries” of her animal neighbors as they make their way here and there.

Moore ends several poems with an expression of wonder. A chance meeting with a yearling moose leaves her “incandescent”; after watching a loon land on the water, she writes, “I can’t catch up / with my heartbeat.” In “Eastern Milk Snake,” four “fearsome feet” of Lampropeltis triangulum triangulumin the compost pile sets the heart “hammering.”

Moore turns to ekphrasis on a couple occasions, most notably her riff on Dahlov Ipcar’s painting Blue Savanna in the Portland Museum of Art collection. In 18 lines she captures the dazzle of Ipcar’s composition where “wildebeest careen over indigo veldts / zebras zig–zag sapphire shards.”

The tradition of the poet / artist goes back at least to William Blake and his “Tyger.” Moore carries it on with her knock–out combo of verse and linocuts. Recalling some of Holly Meade’s woodcuts, a charming “woodchuck non grata” accompanies a poem about the raids the animal makes upon the fresh vegetables at Rebel Hill Farm in Liberty, Maine. Barn Owl Nocturne and Red–Tailed Hawk in Snow emulate Japanese artists.

Earlier this year, granddaughters Maria and Serita sent my wife and me handwritten transcriptions of two animal poems, “The Little Turtle” by Vachel Lindsay and “The Frog” by Hilaire Belloc. They were reminders of how especially cherished animal poems are. With What Rough Beasts, Moore adds to that precious inventory.

— Carl Little