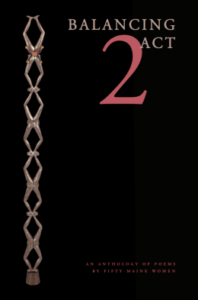

Balancing Act 2: An Anthology of Poems by Fifty Maine Women

Balancing Act 2: An Anthology of Poems by Fifty Maine Women

edited by Agnes Bushell,

Littoral Books, 2018,

160 pages, paperback, $20,

ISBN: 978–0–578–41233–7

How Portland, Maine, four decades ago, got to be known by some of its arts and literature street people as “the Paris of the ’70s” is not exactly clear. I first saw the phrase in 1975, in an enthusiastic letter to some editor. Recently I saw a claim that it first emerged at the Portland School of Art. Anyway, those of us who were there invoked it with appreciative irony during poetry readings and arguments over aesthetics at Jim’s Bar and Grille on Middle Street. Joe and Nino’s Circus Room was still operating a few doors up, amidst the efforts by artists, galleries, street performers, musicians, and, in their own furtive ways, poets, to create mini Greenwich Village in the down, dirty, and dangerous Old Port.

One of the memorable events of the time was the publication of Balancing Act: A Book of Poems by Ten Maine Women. The women’s movement was hitting one of its crests then, I think, and I remember sparring in a friendly way in some Portland living room one evening with Marcia Ridge, one of the editors, about whether anthologies that implicitly excluded men were any nobler than anthologies that quietly excluded women. This was before the 1980s and ’90s institutionalized social activism in art as first hip, then de rigueur, and finally a criterion. The book was collectively admired. Little did anyone know that forty–three years later, one of the contributors would be elected Maine’s first female governor.

Or that it would take that long for Balancing Act 2 to appear. In keeping with the steady expansion over the decades of diligent, competent writing in Maine, this book quintuples the number of poets represented in the first issue, and includes artwork by Celeste Roberge and Joy Drury Cox. The contributors run a full chronologic range from No. 1’s Jane Hendrick and editors Lynn Siefert, Agnes Bushell, and Marcia (Ridge) Brown, to women who emerged a bit later as influential Maine voices, such as Lee Sharkey, Dawn Potter, and Betsy Sholl (Maine poet laureate, 2006 –2011), through Annie Seikonia whose verse has been quietly gracing Portland since the 1980s, all the way to high school student Rachel Ouellette. To name just a few, obviously.

Since Kate Kennedy’s introduction invites us to dive in “any which way,” I went directly to Patricia Smith Ranzoni’s selections, where I was pretty sure I would find a touchstone. And did. While the poems in this book are characterized overall by technical competence (in some cases brilliance), care, and thoughtfulness, Ranzoni’s “7 loons in an evening trim” is transcendent. It’s not just a 25–line tour–de–force of music and syntax comprising a conceit; the depths that loons dive become a figure of this exclamation: “daughters how well / you’ve learned how / to pass your mothers / how not to drown.” It’s one of Ranzoni’s many poems that sound deep in the underused nonrational faculties. This poem took the top of my head off. The whole book is worth this one poem.

But of course, there’s more. I looked to see if Linda Buckmaster had contributed and was happy to see she did. And I’m telling you, she is one of Maine’s largely unsung master poets. Her “Entering the Abandoned Grain Mill at Dusk” is a personal recollection, apparently, of an epiphanic moment during a visit to an old mill building in Portugal. It’s a haunting poem, partly because of its “lengthening shadows” imagery, and more because of its echoing phrasing:

. . . The trail is clear and we have only to follow.

We have only to follow, and the walk, not far, is far enough to move

through field, past barking dogs, along the road and into brushy woods

as the sun’s last red lingers on tree trunks and fence posts. We find

the final approach through dried grasses has been swept clean.

The final approach has been swept clean. Spent seed heads

mark the edges.

Efforts to adapt contemporary American diction to forms like sestinas, or variations thereon with repeating phrases, turn up fairly frequently in recent years; the results almost always seem miserably wooden. But Buckmaster’s repetitions sound not only natural, they actually evoke, indeed create the sense of deep, lingering psychic echo. This is a remarkable, brilliant poem.

More: from, maybe, Robin Morgan’s wing of the women’s movement, come Wendy Cannella’s three memorably enraged poems “L’il Red,” “Ode to a Terrible Joy,” and most emphatically “The Word Slut,” which, we are reminded, was invented not in response to Madonna’s

1980s look, but in the year 1402: “1402, people . . . / But what kind of an asshole writes in his Odes: / She’s ugly, she’s old . . . / And a slut and a scold. / That’s Shenstone circa 1765 and thank god / he’s no longer alive; thank god for sluts like us.” I want to say, “I hear you, sister,” but given my white heterosexual maleness, I’m not sure what further sandblasting that would elicit.

And just to take you in one of the other completely different directions in which the tones and topics of this anthology go, there is Leslie Moore’s “Daddy Long Legs,” one of her startling, heartwarming reflections on the natural world. “We view each other with mutual suspicion,/the bathroom spider through all eight arachnid/ eyes, and I, a two–eyed towering monster,” begins the poem, and she goes on to detail her effort to identify the beast and depict the human–to–arachnid relationship that develops, ending:

My husband once explained my theory of

housekeeping to a niece. Instead of sweeping

cobwebs away, she writes a poem about the spider.

A very wide range of women’s experience is reflected here, and beyond. More nature poems (“A Good Hard Frost,” Elizabeth W. Garber) and family poems (“The Time He Brought Home Venison,” Laura Bonazzolli); poems of grief (“Orpheus,” Laura Trapletti) and of love (“Anniversary,” Susan Colburn Motta); poems of activism (“Dear Chairman Mao, Who Will Speak for the Yangtze?,” Deborah Krainin) and of personal recollection (“first marriage,” Jeri Theriault); women’s poems (“Womanhood,” Shana Genre) and men’s (“When an Old Man Cries for Joy,” Leonore Hildebrandt); and poems that send up reverberations of many kinds (“Red Canoe,” Siefert; “Midwinter Spring with Fly,” Brown).

Reverberations from years ago. 1970s Portland seems, in some ways, almost as far away as 1870s Paris. But Balancing Act 2 is a sign that the present is directly linked to the past. To quote the new governor, we are all in this together.

— Dana Wilde