Snow Chairs, With A W/hole In One, How The Crimes Happened

Snow Chairs,

by George V. Van Deventer,

Snow Draft Press, 2009,

27 pages, paper, $6.00

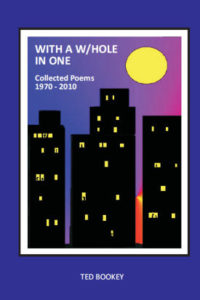

With A W/hole In One: Collected Poems 1970-2010,

With A W/hole In One: Collected Poems 1970-2010,

by Ted Bookey,

Moon Pie Press, 2010,

82 pages, $10.00,

ISBN: 978-1-4507-7

Buy the Book

How The Crimes Happened,

How The Crimes Happened,

by Dawn Potter,

2010, CavanKerry Press,

93 pages, $16.00,

ISBN: 978-1-933880-17-4

Buy the Book

Recently at a state park campground on Long Island, as night came on I heard the different campers who staked down their tents talking around their campfires. Although, for the most part, they spoke English, its shape and form — the vowels and consonants — changed drastically depending on whether I was listening to a Hispanic or Asian family, or a family from New Jersey or New York City. I was struck with the musicality of our language, how the words we use resonate in our mouths, and how that resonance not only reflects our heritage, but also shapes our consciousness of our world.

In rhythm and tone, the three poets whose books I review here are as varied as those campers I heard.

Take George V. Van Deventer, in whose new chapbook, Snow Chairs, he tells of summer nights when “families share each other’s stoop / mixing English and Italian like water to grape.” He writes of how, as a boy growing up in Newark, New Jersey, he danced behind “the organ grinder with his parrot,” how he would hang out “under a lamppost / next to a fire hydrant . . . within shouting distance of home . . . and play kick – the – can, ringalario, drifting through / the freight year.” His language has the earthy immediacy of a street kid who knows that, beneath the rough world, he could survive like a fox, its eyes “blazed wild.” He remembers a fox being killed, the hunter whacking it between the eyes, and it then being reincarnated as a stole that his Sunday school teacher draped over a chair every Sunday. He speaks plainly about his remembrances: “The winter . . . coming / the sky . . . fat and heavy / grey and close in a chilling wind.” I can almost see him by the refracted light of a Coleman lantern, telling his stories to his grandchildren.

If I turn my head, I can also hear the rich, distinct tones of a Brooklyn accent, which fills Ted Bookey’s new book, With a W/hole in One: Collected Poems 1970 – 2010. Listen to someone who delights in words and word play in his poem “Reflections on Hmslf”:

Sufferin’ Reeee – jetionals!

FEEEEEErocious Barars!

Also two moles and of which

One cuts shaving.

The other on the elbow —

Picked at, grows.

& can’t stop smoking enough.

Lucky he’s not a mouse.

His distinct voice — a combination of playful engagement with words and deft shifts in pace and tone, along with his willingness to poke fun at himself and, by extension, many of us who are absorbed with appearances — makes his poems delightful. He has created a wonderful character, Yekoob, who ruminates about the absurdities of world — from Original Sin to loss, aging, and, alas, the falling off of sex. Yekoob is like a camper who enjoys staking up only one side of the tent so the other side flaps. He sets us up to think that he is talking about one thing only to deliver, like a good comic, a contradiction that makes you think twice about what you just heard:

No time left for you to lose

You’d try to find, but knew

How again you’d only gain

One more thing for you

To use again.

But this book is particularly special because it collects Ted’s previous work, all within a lovely cover designed by his wife Ruth. His earlier poems, many about his family, are among my favorites. Textured with his unique blend of angst and humor, these poems charm and challenge us, take the agonies and transform them into hilarities, yet, as they do, never let us forget how much harm and love sleep in the same bed. They clip along at a quick pace, so we have to keep alert to all the shifts and turns. But I could sit by a campfire and listen to them all night. In his poem, “Oral Family History with Heavy Enjambment,” he used the disjunctive quality of enjambment to create his zany family history:

Your father married late in life a women broke his

heart he was young and lost his head I helped him screw it

back we had money how much don’t ask! Easy street we had

a limousine & a maid . . .

A RODENT!!!

fell in a plate of soup and drowned. . . .

Finally, if I turn again, just within earshot of Ted is another voice, one that I must listen to carefully: A woman, who is sitting by her husband (their two young sons not far off, confabulating in their own tent) is speaking. It is the poet Dawn Potter. Her voice has such nuance and range that I fear I am missing any of her precious words. Her new book, How The Crimes Happened, also makes for good campfire reading. It pokes fun — and equally reveres — the rural life in Maine. It encapsulates the exhausting demands of being a mom. It captures the sweet paradoxes of being loved and loving. And, as if sometimes tired of this life, it shifts to Fiends and Goddesses who have it no less easy.

She uses language so carefully and adeptly that listening to her poems makes me feel her reverence for the word. She can sling out beautiful similes, one after another, each building on the previous one, using lovely alliterative riffs like “clinking ice cubes,” and then, with a cavalier shift in tone, toss in a line like: “yes, we did, / even if our attainments were admittedly half – assed and fraught with unexpected chickens / flapping home to roost.”

This tonal shift is always perfectly timed and intentional: It grabs your attention and forces you to see that under the guise of rhetoric, she is actually spinning, slightly under the surface, another tale that finally bubbles to the surface and changes the whole direction of the poem.

She can talk about her son playing in his B – string boy basketball league with what appears to be a cynical edge, describing the spectators as “heavy – set / mother and fathers, parkas unlashed, tired haunches, / roosting on the narrow benches,” as the

“eighth – grade girls cluster in a corner / sucking up Mountain Dew,” as if she is a bystander, separate from them. Then, in the middle of the poem, as her boy’s team is being routed by the opponents, she realized that each parent wants his or her son to do well, and “the very air begins to smell of love — / not just for their own sons, but for every clumsy, familiar / body on the floor, for every boy who ever built Lego racecars.” By the end of the poem, we too are transformed into fans, knowing full – well the boys will lose, but not caring because “they belong to us.”

She can speak as a mother, as a wife, as a lover, as a friend, shifting and changing the tone and shape of her poems to fit the point of view and the subject. In a poem about her hometown, Cornville, she imagines herself as a woman driving along a road, looking at the “for – sale lineup / not of corn but of flat – bellied pumpkins, and her son listening to Joe Castiglione, the voice of the Red Sox, and then manages to weave in Cinderella’s godmother, Grendel, Oedipus, Home Depot, and a Rottweiler, his “head thick as brick,” and bring them together in the final stanza. It is stunning. But she does it again and again. In poems about the Fiend (Satan) and Paradise Lost and in poems about loving her husband, which are both tender and ironic, poems that any of us who have loved someone over decades can fondly identify with, she manages to walk the delicate line between her urge to belong and the inevitability of loss. In the poem “Eclogues,” she turns to her husband, as she notices how “sweat rises from [his] sunburnt neck, salt and sweet,” and then proclaims:

My love. Marry me, I say. You cast

an eye askance and shrug, I did.

She ends the poem musing that

the maples redden,

shrivel, and die.

Nothing needs me,

today, but you,

sweet hand,

cupping the bones

of my skull. Alas,

poor Yorick, picked clean

as an egg.

These are poems that force us to look at the night sky and see in it its majesty, its beauty and its darkness. Our humanity is not a solitary enterprise — she knows it, Ted knows it, and George knows it. They are poets whose voices, although distinct, remind us of the paradoxical, absurd, and yet loving nature of our world.

— Bruce Spang