Our latest Winter 2022 Latin American Issue of The Café Review continues our mission to bring Maine poetry to the world and poetry from around the world to Maine with our special Latin American issue featuring poetry by Magda Portal from Peru, Ernesto Cardenal from Nicaragua, Jorgenrique Adoum from Ecuador, Carlos Maria Gutierrez from Uruguay, Juan Gelman from Argentina, Fayad Jamis from Cuba, Roque Dalton from El Salvador, Nancy Morejón from Cuba, Gioconda Belli from Nicaragua, Daisy Zamora from Nicaragua, Raul Zurita from Chile, Sara Vanégas Coveña from Ecuador, Reina Maria Rodriguez from Cuba, Elicura Chihuailaf from Mapuche, Chile, Victor Rodriguez Núñez from Cuba, Alfredo Zaldivar from Cuba, Maria Vázquez Valdez from Mexico, Eduardo Bechara Navratilova from Colombia, Yana Luila Lema: Kichwa from Ecuador, Mardonio Carballo from Nahuatl, Mexico, Livia Natalia from Brazil, Jean Jacques Pierre–Paul from Haiti, Claudia Guerra Castillo from Zapoteco, Mexico, Stephanie Borges from Brazil and Natasha Felix from Brazil. Kristin Dykstra, Laura Cescarco Eglin, Alba Stacey Hawkins, Katherine M. Hedeen, Tiffany Higgins, Victor Rodriguez Núñez, Margaret Randall, Kathleen Weaver and Camila Yver contributed the translations.

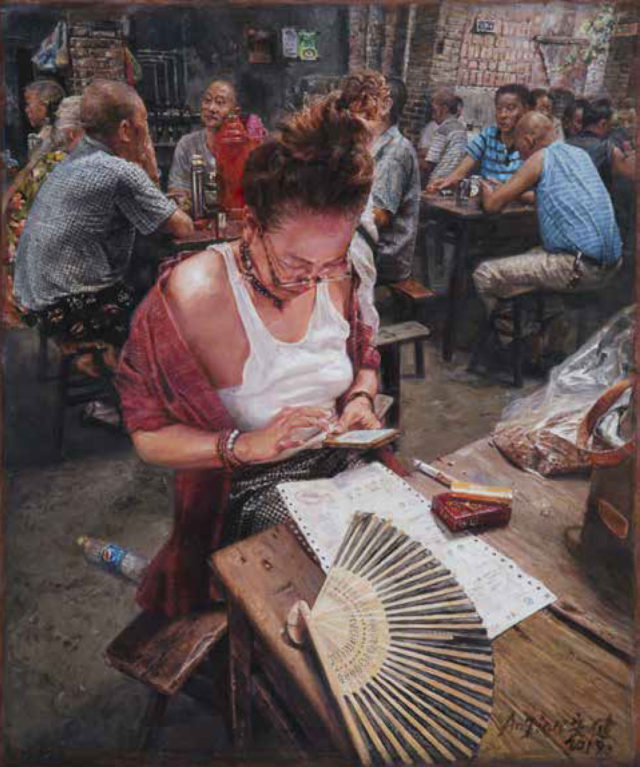

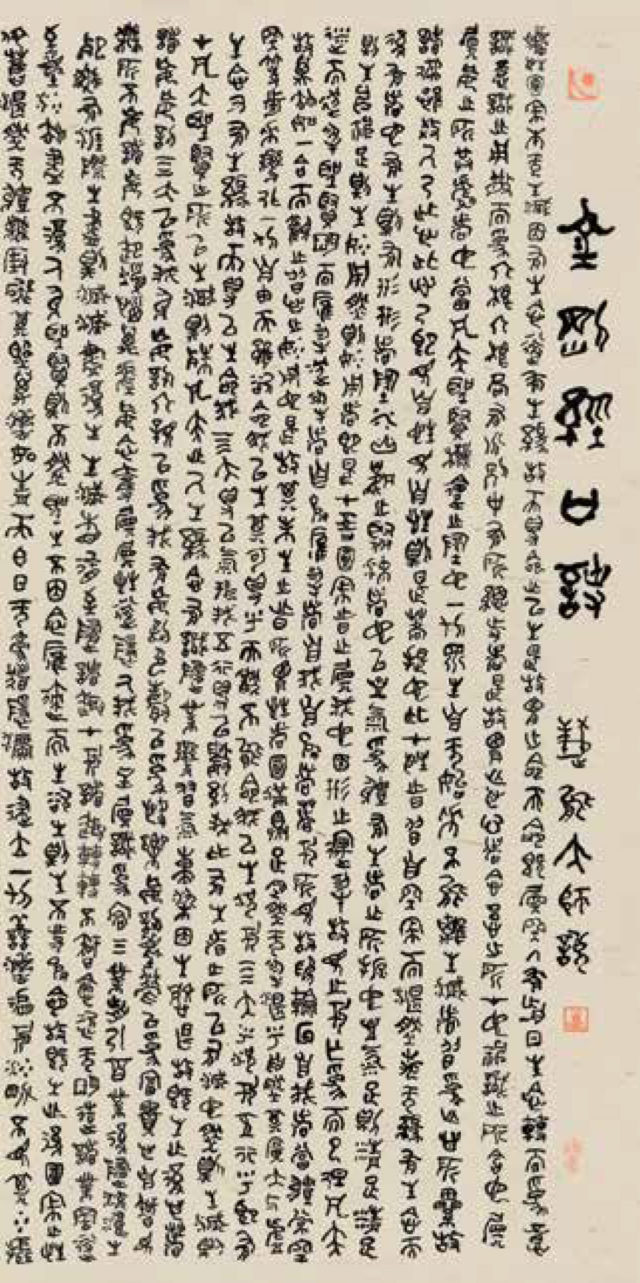

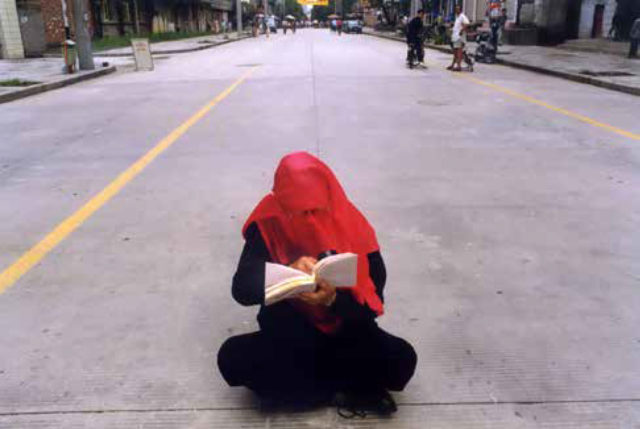

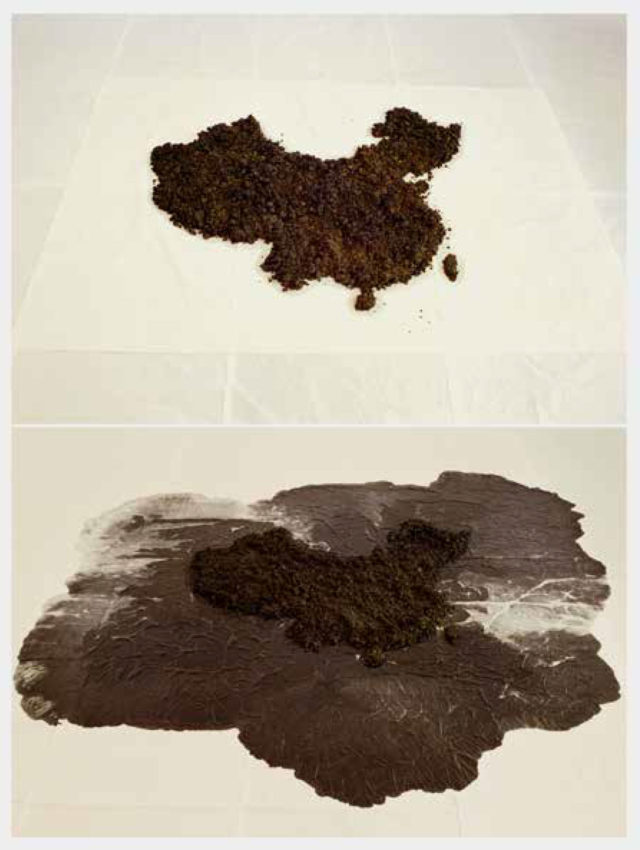

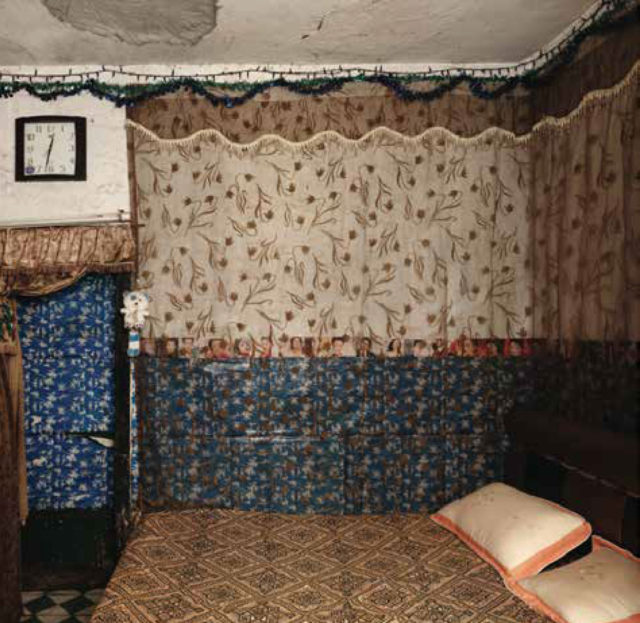

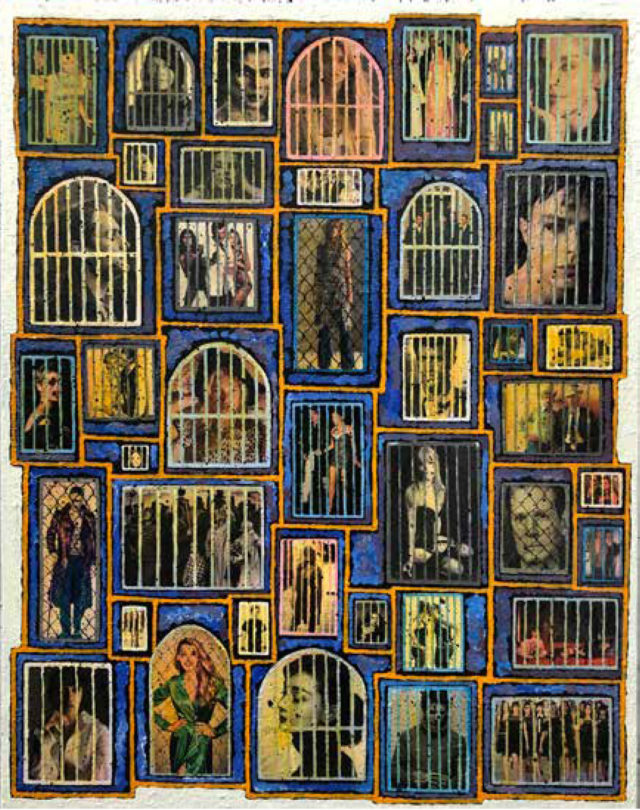

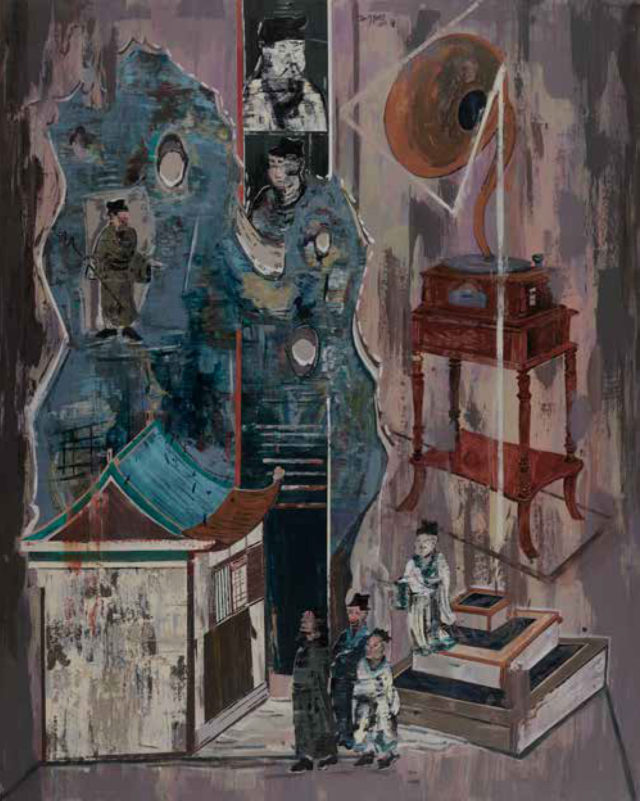

This issue also features artwork by Alfonso Fernánde Acevedo, Jorge Arcos, Josefina Auslender, Andres Chaparro, Felipe Ehrenberg, Pedro Fuertes, Catalina Gomez–Beuth, Sofia Hinojosa, Dora Lopez, Coca Milán, José Rodiero, Alfredo Rostgaard, Carlos Solis, Nina Tichava and Melvin Toledo.

As always, we are an all volunteer micro-pub producing printed publications quarterly from Portland, Maine. If you love our issues and work here online, support us by donating or subscribing. Without our subscribers, we would not exist!

Introduction by Guest Editor, Margaret Randall

When Steve Luttrell invited me to guest edit this issue of The Café Review by curating a sampling of Latin American poetry in translation, I eagerly accepted.

It’s been a labor of love. I mean that quite literally. Neither I nor any of the poets or translators were paid for our contributions. This speaks to the marginalization of the genre in our national culture. We appreciate venues such as this one for making poetry in translation available.

With a limited number of pages, I knew I would have to make hard decisions. I also knew I would have the opportunity of introducing an English reading public to some of the continent’s great voices. My first consideration, as always when working on an anthology, was quality. I chose poets whose work I feel is beyond simply good. I featured poems that take risks, that break with tradition and move into new areas of poetic voice, or those that take traditional poetics in unexpected directions.

Secondarily, but also important to me, I sought equal representation of work by women, as well as poems by indigenous poets and poets from Brazil (although the latter required my depending on those who translate from the Portuguese, a language I don’t know). Afro–Brazilian poetry by women was a revelation. Most Haitian poets write in Creole or French, but I was fortunate to find one who also writes in Spanish and sent me poems in that language which I was able to translate. I wanted to represent as many countries as I could. And I wouldn’t indulge in tokenism with regard to any of these groups. I know that if we look, we find what we’re looking for. Still, the selection you hold in your hands represents a fraction of the extraordinary poetry of the Americas south of our border.

The responses of the poets I contacted were gratifying and I’m grateful for their generosity and confidence in my ability to render their poems in such a different register. I have also been able to count on some other very fine translators and thank them for their collaboration. This is a small sampling. And, as anthologies tend to be, absolutely arbitrary. I have wanted to include some of the iconic names — Ernesto Cardenal, Roque Dalton, Juan Gelman, Jorgenrique Adoum, Raul Zurita, Nancy Morejón, Victor Rodriguez Núñez, Reina Maria Rodriguez — and also newer voices.

I hope this collection will speak to the variety of poetry being written throughout Latin America from a great diversity of cultures. Commonalities exist between the nations of the continent, but vast differences mark them as well. The great guerrilla poets of the 1960s and ‘70s were never subject to the dismissal or blatant condemnation that poets writing about social issues in the United States suffered under McCarthyism, the residual damage of which continues to plague us. Nicaragua’s Rubén Dario, Cuba’s José Marti, and other modernists sounded an antiimperialist message that reflected what the global south experienced (and continues to experience) from the United States. Surrealism is an influence that has lingered, blending with homegrown magic realism to produce a particularly Latin American variety of the tradition. Catholic mysticism has also flourished, sometimes in syncretic combination with African or indigenous visions.

Poets such as César Vallejo, Gabriela Mistral, Jorgenrique Adoum, Roque Dalton, Ernesto Cardenal, Juan Gelman and Raul Zurita changed language itself for poets writing in Spanish, and their influences can be felt. Cardenal produced a conversational poetry, what he called exteriorismo, the echoes of which can be heard in many subsequent voices. Brazil’s concrete poets of the 1960s left a palpable mark. And now that poets from the many hundreds of indigenous nations with rich linguistic traditions (written as well as oral) are beginning to be acknowledged, the rhythms of holistic cultures found in their work add to a rich and complex mix.

Conversely, US poetry has also influenced that in the global south. Whitman, Pound, and Williams were studied by many of the great Latin American poets of the past century. The Beat aesthetic can be heard in Colombia’s Nadaistas and other groups. The raw intimacy of poetry being written by women and LGBQT poets — especially those of color — encourages the same groups to raise their voices throughout Latin America. Slam poetry and hip–hop have had an impact. Latin America’s important poetry festivals bring poets from various latitudes together and have broadened a fruitful exchange. Every two years, Languages of the Americas, hosted by the University of Mexico, has put indigenous poetry on a par with that written in the European languages. Over the past half century, poetic influences in both directions have emerged as poets have been able to read one another’s work in better translations.

One of The Café Review’s requirements for this anthology was that the poems be unpublished in English translation up to now. This is true of all with the possible exception of the two by Ernesto Cardenal. Most of that poet’s work has appeared in English and, although I did the two translations included here, I am not sure whether or not the poems have been previously translated.

My experience translating poetry from Spanish into English began in the 1960s when Mexican poet Sergio Mondragón and I edited El Corno Emplumado /The Plumed Horn, a bilingual literary quarterly out of Mexico City. We were motivated by a need for interhemispheric communication, and for eight years produced issues averaging 200 pages, in which we showcased such important poets as Ernesto Cardenal in English and Allen Ginsberg in Spanish. We were proud of deconstructing cultural borders. And we presented some of the best work of the era. Almost three quarters of a century later, the journal is still an important reference.

Sergio and I were a good team. He took the lead when we translated from English into Spanish; I when we worked in the other direction. When I reread our translations from those years, though, I realize how much I had yet to learn about recreating poetry in another language. Translation is not mere substitution. It is a complex artform, sadly one that is rarely given the respect it deserves. The translators I have invited to join me here understand this as I do.

My hope is that this selection will whet readers’ appetites for more of each of these poet’s work.

— Margaret Randall, Summer 2021