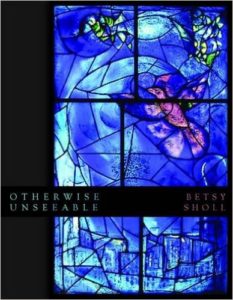

Otherwise Unseeable

by Betsy Sholl,

by Betsy Sholl,

University of Wisconsin Press, 2014,

78 pages, paper, $16.95,

ISBN: 978-0299299347

Buy the Book

How can we properly cherish the beauty in the world while also embracing its harsh realities? In Otherwise Unseeable, Betsy Sholl’s eighth book of poetry, the author investigates this paradox in both personal and political narratives, with a hungry lyric that could only come from someone who’s survived much. Whether re-writing a Brothers Grimm fairy tale, painting a portrait of a burnt-out gambler, or reconciling feelings over the loss of a parent, Sholl offers a rich tapestry of insight and humanity.

Sholl’s mastery shines in her ability to show us a well-known idea from a new angle. This is most evident in poems that take on fairy tales, as in “Rumpelstiltskin,” “The Woodcutter,” and, especially, “Frog to Princess” which retells the Frog Prince story from the perspective of a frog with no ambitions of becoming royalty:

Yes, I’m a croak cloaked in green slime,

a bulging gullet, a mouth full of mud.

But with great quads, Princess, and a tongue

quicker than flies. If you kiss me you’ll taste

where life comes from, its quagmire scum . . .

. . . Not your marble halls and canopied bed . . .

With great music and humor, Sholl introduces us to a re-envisioned frog who is proud of his slimy grit and has come to teach the princess a lesson, noting that her “world paves over what it needs most.” The frog is the gut, the instinct for telling “whether the world’s going on or out.” He warns: “Without me and my kind, Princess, no pond baubles bubbling up new life.” Wishing for a handsome prince is actually the princess’s downfall, because she is waiting for something better to come along while ignoring the muck of life. The frog insists that the princess’s dream of the prince is “a curse, the world’s hearse. I’m what you need . . . the world’s wettest sex, green putty — right here — in your hand.” With this retelling, Sholl asserts that we need to not only accept life the way it is, warts and all, but also to seek to understand the messiness. By wishing for something else — a different lover, a bigger bank account, what have you — we miss the chance to create our lives, with “green putty,” in the often-grimy reality in which we exist.

Another element consistently present in this collection is that of wind as a visceral image to depict life itself and its never-ending changes. From the “voice of mist” that enters in “Alms” to the tumultuous currents that create music in “Wood Shedding,” “Bass Flute,” and “The Aging Singer,” to an exacting characterization in “The Wind and the Clock,” one cannot read this book without becoming roused by “its little eddies.” In particular, “Vanishing Act,” a poignant lyric on the looming reality of death, starts quietly:

Over the phone we’re already bodiless,

though remember, Love, sound has a source

and even a kiss made of mist

can touch a cheek and lodge in the mind.

But the lyric soon builds. The kiss of mist demonstrates how even a whisper can make an impact and set off a flurry of thoughts and emotions, and as the poem continues, the speaker frets over whether she or her partner will die first:

I can’t help fretting about our next porous

existence, which one of us

will go first, last breath disappearing

in a crowd of molecules,

while the other is left alone

with a closet full of empty clothes.

The porous existence extends the wind/air metaphor, depicting death as a process of evaporating into another dimension: That imagined last breath that vanishes into molecules might as well be a crowd of ghosts. But to land, finally, on the image of empty clothes makes the speaker’s fears heartbreakingly solid.

Later in the poem, she states plainly: “Until it’s our turn, what do we really know?” It is a haunting truth of being human that we don’t know what death and beyond will be like, and yet we have to live with this ominous unknown, and what’s more, accept the end of our beloveds. However, the speaker continues to say that “even despair . . . is good,” and can inspire us to live more fully, even “cause a woman / warming herself under five skirts / to throw back her head and sing.” With great skill, here, Sholl gets at our fear of death while still managing to invoke hope. It’s another version of the message from the frog in the swamp: Sholl challenges us to stop resisting and step into the difficult feelings that hold us back from actually living.

But to limit the value of these poems to their spiritual message would be a disservice. It’s Sholl’s ability to withhold sentimentality, execute dynamic language, and to choose images strategically that make her poems powerful. What’s more, this book inspires the writing of poems — what could be a better gift than that? Amongst the many images burned into my memory — a deaf woman pounding the side of her head, a tramp stamp tattoo in the shape of a dog, a fragile parent in form of a tea cup — the simple image of a gold finch seems most apt at describing the poet herself: “How fragile genius is, anxious, always ready to leap from the sill, always an eye out for the informer.”

— Kristen Stake