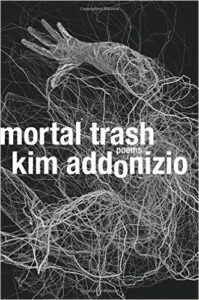

Mortal Trash

Mortal Trash,

Mortal Trash,

by Kim Addonizio,

W. W. Norton & Company, 2016,

107 pages, hardcover, $25.95,

ISBN: 978-0-393-24916

Kim Addonizio is a master at roving narrative poems that take radical shifts in tone, context, and syntax, and that never fail to pack a punch. Her latest book, Mortal Trash, offers a torrent of images and experiences from someone well aware that time is limited and life is fucked up. Bursting with original language and idiosyncrasy, the book reads like the diary of a riot grrrl grown wise, still teeming with angst but also sorrow and humility.

The best poems are the ones that promise insight or advice but derail themselves off topic, like “Internet Dating.” It begins with the typical complaints, yet with clever, not-so-typical delivery:

I am tired of kissing nematodes,

splitting the check with scorpions,

listening to the spiritual autobiographies of slugs

over an infinitely repeated series

of banal gestural codes.

Mixing quotidian and fairytale with scientific language — like nematodes (tiny, invisible worms) and gestural codes (subliminal images) — creates a disorienting effect. Anyone who’s been on a dating site will tell you how lonely and clichéd it is, but by using this kind of technical writing Addonizio extracts just how impersonal it can be. Then, however, the poem takes a personal turn, as the speaker continues:

Get out of my inbox.

I feel violated. Not in a good way.

There’s no one I want to inhale into my alveoli

like I did with you. There, I just made you

into a cigarette.

We are quickly taken into second person, wherein the “you” that first appears as an offending online suitor quickly morphs into a lost love. Then the speaker’s address to the former lover takes over, asserting: “I want another you, and then another.” We are pulled into neurosis that fuels the speaker’s internet search. She continues: “If I read your profile online, I’d never write you. But I miss all the sides of your face.” As at the start of the poem, the poet seems to be commenting on how arbitrary it is that we allow algorithms to determine something as imperfect and subjective as whom to fall in love with.

The most eviscerating poems in this collection — “Seasonal Affective Disorder,” “Manners,” “Introduction to Poetry,” “Party,” “Divine,” “Candy Heart Valentine,” and “Florida” — are so sharp and dynamic — what with the “inner space heater / and TV and washing machine . . . all going at once” — it would not do them justice to share only a few lines. Other poems, however, offer an unexpected, softer lyric, like “Invisible Signals,” in which the speaker reflects upon the connection between her life and her friends’ as she sits by the East River in Manhattan:

. . . I like to think of my friends

imagining me so we’re all together in one big mental cloud

passing between the river and outer space. Here we are

not dissolving but dropping our shadows like darkening

our handkerchiefs on the water.

I love the straightforward image of a group of friends encased in a cloud floating over a river, and the picture of their shadows casting like handkerchiefs onto the surface of the water is just breathtaking. The poem continues by referencing each friend in her particular struggle in life:

One crying by a lake,

one rehabbing her knee for further surgery. One

pulling a beer from the fridge, holding it, deciding.

One calling the funeral home, then taking up

the guitar, the first tentative chord floating out,

hanging suspended in the air.

The image of each woman shows a transition point in life — another reminder of mortality, a theme that runs throughout the book. These moments of reprieve from Addonizio’s more acrobatic poems strike a balance for the reader. For example, a section of fourteen sonnets mid-way through, while still tenacious in attitude, is condensed enough to leave space for contemplation.

Behind the layers of Addonizio’s poems are three central qualities: toughness, vulnerability, and sadness. From refrains of “I feel” to text-speak to Shakespearian iambs, Addonizio finds the sacred in the profane, and like the Buddha, sees suffering everywhere. If her poems leave you tongue-tied, as they do this reader, “Manners” demonstrates, albeit ironically, how to convey gratitude:

Thank you for not sharing with me

the extrusions of your vague creative impulse.

Thank you for not believing those lies

everyone spreads about me, and for opening

the door to the next terrifying moment. . . .

— Kristen Stake