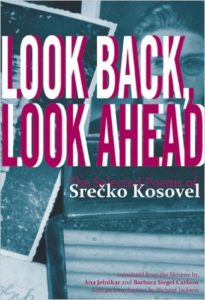

Look Back, Look Ahead: The Selected Poems of Srecko Kosovel

by Srecko Kosovel,

by Srecko Kosovel,

Translated from the Slovene by Ana Jelnikar and Barbara Seigel Carlson,

Ugly Duckling Presse, Brooklyn, NY, 2010,

220 pages, paper, $17.00,

ISBN: 978-1-933254-54-8.

Buy the Book

Most English speakers have probably not heard of Srecko Kosovel or hundreds of other poets who wrote in their native tongues, who spent their lives struggling to bring light and justice to a primarily imperialist world. It has been the work of translators to bring these voices into our hearing and our hearts, re-building them carefully and gently so that poets like Kosovel, a Slovenian, live for us again. As the translators say in their notes:

. . . we came around a dirt road to a high stone wall with a

fig tree on the other side whose high branches were laden

with fruit. One of us climbed the wall and, balancing just

so, reached up for a few plump figs and handed them down

to the other. So it has been translating Kosovel’s poetry: to

be given this sweet fruit born of what we can never wholly

recreate, and handing it down as best we can. (xxi)

While this is not the first collection of Kosovel’s poems, it builds on previous collections and offers previously unpublished poems by a young poet who wrote with a tenderness and ferocity beyond his years, as in “Who Cannot Speak”:

Who cannot speak

has no need to learn.

You look for a new word —

today it’s unclear

which word it is.

You must wade

through a sea of words

to arrive in yourself.

Then alone, forgetting all speech,

return to the world.

Speak as solitude speaks

with unutterable mystery.

Kosovel had published only some 40 poems at the time of his death, but he left approximately four thousand poems and fragments, more than a lifetime’s work for many poets. Kosovel died in 1926. He was 22 years old. Growing into his voice at a turbulent time in European history, he wrote in a wide range of styles: traditional pastoral poems that evoked his deep ties to his homeland, political poems that stoned the impenetrable walls of nationalism, experimental work that included mathematical symbols, unorthodox word placement, and other avant-garde experiments, while including stunningly lyrical moments. Here is the voice of a poet coming of age at an earth-shaking time. His work spins on a wheel of changing politics, social upheaval, new technologies, and alternative spiritualities. Kosovel gave voice to an age even as he stretched his work to include all these changes. His vision was local and global, personal and universal.

The work of Carlson and Jelnikar in bringing these poems to us feels like the recognition of poets for a lost friend’s work. They bring examples of Kosovel’s varied voices, yearning or strident, challenging or fearful. Their translator’s notes help us understand the extreme attention demanded by the work of carrying the complexities of sound, rhythm, and underlying levels of meaning of a poem while attempting to be true to the voices of both languages and the poet. Poems are chosen to represent the whole body of his work, not merely the comfortable. The introduction, by Richard Jackson, and the afterword, by Ana Jelnikar, give us windows into Kosovel’s life and times and provide us with some historical context for his writing. A contemporary of James Joyce, who was living in Trieste as the young poet was lighting the torches of his poems, and Rilke, who was writing his elegies nearby in the castle at Duino, Srecko Kosovel has been called “the greatest Slovenian poet of the twentieth century” by Tomaz Saluman. It is only the work of dedicated and sensitive translators that allows us to hear him. They deserve great thanks.

Often the task of a reviewer is to make judgments based on his or her personal response to a poet’s work. In this case, I can only say that I feel fortunate to have spent some time with the translators in Slovenia a few years ago and the beauty of the place is deeply haunting. Through these poems I will return there again and again:

One Word

I wish I could say one word

just like the spring wind

softly enters your heart.

I wish I could say one word.

But look, I have nothing else,

my heart is an altar cracked in half.

My words are like wounds,

each one of them bleeds.

Dreams don’t vault into this dark,

only black walls’ rough edges

rise like memories of old times

into the deserted terror of the night.

But still there is, there is still

one word — one word at least!

Come, you night – wounded man,

So I can kiss your heart.

This collection is your opportunity to hear a voice that could have been lost. Do not walk away.

— Michael Macklin