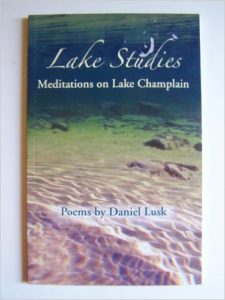

Lake Studies: Meditations on Lake Champlain

by Daniel Lusk.

by Daniel Lusk.

Lake Champlain Maritime Museum, 2011,

96 pages, softcover, $14.95,

ISBN: 978-0-9641856-8-5.

Buy the Book

From the preface of Daniel Lusk’s Lake Studies, we learn that its poems are the result of “two years of research, of the underwater character and human and natural history of Lake Champlain.” For some of us, this carries the enticement of works bathed in natural history, sprinkled with science. Not quite. These are “works of imagination,” not to be confused with “history, archaeology, journalism or other science.” They’re poems. And yet, how do two years of research into a big lake manifest as poetry?

By going under. There, Lusk has us peer into darkness and hear sounds muffled. There is less clarity and more mystery; all is otherworldly. But before the poems actually dive, we wet our feet at or above the surface. There, Lusk often draws our attention to sound, as in “Story”: “Whisht! Listen.” In this case, the soundscape is an ancient one of thunderous, shrugging glaciers. Whispers, voices and cries, populate another early piece, “People,” and in a sequence of poems about nautical disasters, the sounds at the surface are wild and cacophonous, mostly human, soon stifled forever.

Lusk gives us bearings before the dive. A map is a logical tool for this, and a graceful 18th century one accompanies “Drowned Lands,” our first bird’s-eye view of the “winding, riverine road” along the southern half of the lake (the only map or aerial photo in this collection of images and text, regrettably). We encounter familiar animals — egrets, mallards, otter, and mink. Here, as elsewhere, though, Lusk inventories so much in the way of species or cargo that he often distracts from the narrative.

The lake setting established, Lusk takes us down with the piece “Nocturne”: “When we go below, / we almost expect to see the stars / . . . fixed in their places along the bottom.” The poet applies philosophical ideas with a deft and wry touch, as in “Salon Noir,” in which he re-imagines the light and shadows from Plato’s Allegory submerged. In “Lake Apparition,” he merges monster, silence, and shadow: “The lake, like our dreaming selves / redolent of secrets / wondrous and perilous.” His descriptions of fish (sculpin — “Full-lipped / as tulips in their turbans”) led me to imagine a new breed of field guides in which species descriptions would be penned by poets, not scientists.

Most of this succeeds as a multidisciplinary work “of imagination,” in which facts and myths are woven together. And, I was pleased, as a student of biology, to see ecological and evolutionary concepts referenced in the poems. For instance, the introduction of the invasive zebra mussel to the lake ecosystem and the irony of the resulting clearer lake water is addressed in “Seeing the Bottom off Thompson’s Point.” However, this phenomenon, one of the greatest ecological tragedies of many lake ecosystems in North America (“mistakes we made / in our youth”) is too briefly explored in only one poem, the shortest in the collection. Elsewhere, a line like “When evolution was yet to come,” which concludes an otherwise lovely elegy to ancient, fossilized life, is puzzling, as it suggests that this process began only when larger multicellular organisms appeared on land. The attempt to merge science and poetry is appreciated but sometimes falls short.

It is the more comprehensible human history of vessels and people that is conveyed most effectively, and then fixed in the lake mud. This long, relatively narrow lake has been crossed countless times; not all attempts succeeded. Lusk reminds us that when we cross water, we cross over a place to which we do not belong: a tomb, so easy to overlook. These poems take us there, from riotous squalls on the surface to the dark, muted lakebed of unseen wrecks and forgotten history.

— Christopher Hoffmann