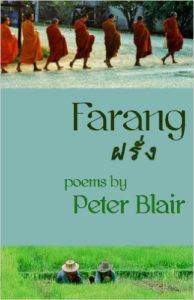

Farang

by Peter Blair,

by Peter Blair,

Autumn House Press, 2009,

64 pages, paper, $14.95,

ISBN: 978–1–932870–34–3

Buy the Book

“Farang,” we quickly learn in Peter Blair’s book about his years in the Peace Corps, means “foreigner” in Thai. The clear images of these melodic narrative poems evoke the legacy of the Vietnam War years, the tensions between Thais and ex – patriot Americans, the struggle to cobble together a pathway between cultural differences, and the lyrical beauty of Thailand and its peoples.

The book introduces the first of its four sections, “November Full Moon,” with the poem, “Discussing the Dream of Culture with Professor Kwaam,” in which an ethereal, clean – shaven, smiling Professor Kwaam pontificates on Thai and American cultures — “two dreams / of one world, the Dharma. A few months ago / he taught me Thai and how to read palms: / A good way to hold hands with a girl. He winked.” The novice poet – traveler is in need of instruction:

Noodles slip off my novice chopsticks.

My soup darkened by soy sauce, peanuts,

sugar, the strands disappear in my bowl.

Kwaam’s noodles twine in clear broth.

Of course, the poet meets a girl. Her name is Siripan. She’s young and beautiful, a school teacher who instructs the poet in vocabulary and demonstrates the ramwong, a kind of waltz, “spinning / through all the positions that turn / a man and woman into blossoms.” But Siripan is already lost, drifting from her family, which does not approve of her dating farangs. Siripan and the poet share stories of their fathers and grandfathers. “They traveled far to find their wives,” Siripan says poignantly. “Our kiss feels like an ocean, / its waves breaking on opposite shores.” So far no one has traveled far to marry Siripan, who appears later in the book only as a longing, a memory.

After visiting a Buddhist temple, the poet tours the bars and brothels of Bangkok, the Angel City, with his boorish American friend Harry, who “tramples / his shadow with his feet / seeking all joys but wisdom / among the metal – grated storefronts, / the butcher – shop, fortune – teller, apothecary, serving the bodily / charkas of the city.” Leaving Bangkok for the countryside, the poet is haunted by ghosts and nightmares featuring Kukrit from The Ugly American, and wakes to the slow turning blade of his ceiling fan: “farang, farang, farang.”

In section two, “Up – country,” the poet – narrator keenly observes scenes of village life: He visits temples on whose walls human figures “pursue their karma”; he joins in the rice planting, standing ankle deep in the fields beside the buffalo; he attends a village fair where he is accosted — farang! — by village youths and wins an ivory Buddha which “hangs on my chest, / smooth as a stone that’s been sunk / in flowing water for 25 centuries.” In “In the Hot Season,” a boy not much younger than the poet’s own twenty – one years floats on the river in the noonday heat. This poem, exemplary of Blair’s best, describes a boy floating on “wide, brown water” in a river “starved of rain”, where tree roots “show through like gray ribs / near the banks.” The boy’s canoe is merely a packing tin “emptied of bamboo shoots.”

The poem’s easy cadences foreswear meter and rhyme for subtle alliteration — “gunwales gleaming,” “wide, brown water” — and strong, graceful lines and syntax, with line breaks punctuating the unfolding narrative, following the grammatical units of meaning. While not especially playful, inventive, or surprising — highly valued qualities in much contemporary poetry — Blair is adept at seeing beneath the surface of the sensory world to the feelings and desires of the boy, the boy’s pleasure in a lazy day on the river, his cotton shirt “a white flag draped over the side, signaling / his surrender to a day without desire.” Blair imbues the boy with the deep qualities of his culture: When the boy’s “eight – fold path lies across / low water cradled by gnarled hills,” he becomes an emblem of his culture’s Buddhism. The final stanza zooms out, giving the reader a wide – screen view:

As the rumbling, spattering caravan

of trucks, buses and tuk – tuks pass

over him on the bridge on their raucous

way to Bangkok, the Angel City,

he floats diamond – bright and solitary

in the middle of the sweltering town.

Halfway from either bank, he finds

the bright center of the afternoon.

And the poet, too, finds the bright center of the poem.

At the close of this second section, the poet travels with his students by bus to the Gulf of Siam, where Ampon, one of his young students, has promised to reveal his secret beach near his house there. But then, suddenly, the festive occasion turns hollow and ghastly: Ampon drowns.

Word spreads through the palms, mangoes

and village streets. His father descends stairs

under his house, walks out into the light,

watching me. My skin never feels so white.

In the house, his mother wails, prepares the body.

“My skin never felt so white” is one of several striking expressions of the poet’s own otherness. The moment of silent confrontation between the father whose son has died and the poet, the climax of these first two parts, has its formal complement in sections three and four, “The Dream of Culture” and “The Land of Transit.” Among Blair’s reflections on the two cultures, he tells us that word has come from the American Consul of his own father’s death in Pittsburgh. He is now the fatherless boy, the one abandoned.

Back in the States for the funeral, at the close of this tender, sensitive collection, the poet stands awkwardly at O’Rourke’s Bar and Grill with his old classmates. And once again, this time to the big, hairy – chested American boys he’s known since grade school, he finds himself farang.

— reviewed by Zara Raab