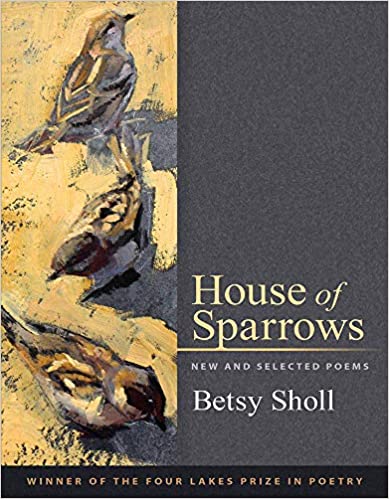

House of Sparrows: New and Selected Poems

House of Sparrows: New and Selected Poems, by Betsy Sholl.

University of Wisconsin Press Poetry Series, 2019,

176 pages, paper, $18.95,

ISBN: 9780299323042

The regard with which Betsy Sholl and her work are held within the Maine literary community was evident at the book release event for House of Sparrows: New and Selected Poems (University of Wisconsin Press, 2019). Longfellow Books in Portland was so packed that evening that I stood in the back with friends to listen to Betsy read. That’s right — standing room only at a poetry reading! Not only that, but the crowd included recently inaugurated Governor Janet Mills. Putting aside the beautiful thought of a poetry-loving elected chief-executive, consider what it says about a poet and her work that she has the ear of such a person.

A New and Selected Poems is a big deal for any poet. Sholl’s is an outstanding entry into a significant body of work. Reading these poems from start to finish (which, as is often the case in a New and Selected, means new poems followed by selections from previous collections in chronological order) it is easy to get a sense of the continuity in Sholl’s work. At the same time, just looking at the words on the page shows the increasing precision and control with which she is working: there is more space in the more recent poems. These poems approach nearer and nearer the clarity of figure flickering in all truly great poems.

Eschewing closed forms and closed ideas, Sholl’s poems often furl multiple subjects, and the images, feelings, and thoughts associated with them, into skillfully braided meditations. One of the new poems that seems emblematic in this way is “Walking Paradise Blues.” In three sections, each with four three-line stanzas and a final couplet, the poem combines references to Dante, anecdotes of Chicago blues musician Walter Horton, and reminiscences of the poet’s grandmother into an expanding exploration of all that lives within the African-American- originated term, blues.

These poems do expand, even when their focus is narrowed. The opening poem, “Apple,” begins, Frost-like, in an orchard: “Crisp press of ladder rung on instep, / tree sway and dappled light, then stem twist / and the weight of apple in hand — . ” From here it moves immediately into the kind of question Sholl poses in poem after poem: “reaching through that leafy green, did we ask / what else we were after ? . . . ” In nine short stanzas, the poem plucks and samples the ripe and contradictory symbolism of apples, before it ends in a morally ambiguous anecdote about a family dog chewing up a perfectly formed wooden apple and being banished to the yard, “as if once down the stairs / he wouldn’t happily enter that bright world / of rock and dirt, nuthatch, beetle, squirrel.”

Many of these poems ask questions about justice and responsibility, as in the newer “Making Dinner I Think About Poverty — ” or the older “Back with the Quakers,” yet they are not “political” poems. What is the proper descriptor for that human substance and force that is deeper than, yet drives, social action ? Spiritual seems too thin and marketable. Moral too mentalizing. Religious too external and artificial.

Soul is the right word, I think. Many of Sholl’s poems mention musicians and songs. Jazz and blues and gospel seem to be touchstones for this poet, and that makes sense. In “A Song in There,” Sholl, who is white, even calls “the old bluesmen” “my heroes” and “my mentors.” Hers are not confessional poems, but Sholl makes passing references to a childhood and family where feelings — and the ways we express them, including with words — were kept locked away. The music of those old blues and gospel artists is the antithesis of such repression. To give artful voice to the full range of one’s humanity seems the essence of soulful musical expression — and of these articulate, soulful poems.

While recently reading Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “Why We Can’t Wait,” about the tumultuous and pivotal year in the Civil Rights Movement, 1963, I was reminded of the wonderful term “soul force.” Derived from Gandhi’s philosophy, “soul force” draws power from what is deepest and best in our humanity in order to confront, and overcome, violence and injustice. Is not poetry itself a form of soul force ? When it comes to Sholl’s work, at least, the term is apt. Her poems express something alert and hungry and hurting and wise. They brave the clarity of truth. They are open to the world. They probe the mysteries of joy and despair, of light and / in darkness. They are the work of someone considering what it might really mean to love your neighbor as yourself.

As she writes it — to conclude that poem about Dante and a Chicago bluesman and a warmly resilient grandmother —

Soul, I’m talking about, what big Walter

blew through bent notes, lonely so you know

somebody’s been down that road before.

Lord they sang. Wore out how many shoes —

one eye fixed on the grit, one on the stars.

— David Stankiewicz