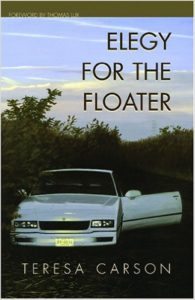

Elegy for the Floater

by Teresa Carson,

by Teresa Carson,

CavanKerry Press, 2008,

84 pages, paper, $16,

ISBN -10: 978 -1- 033880 – 07- 05

Buy the Book

Suicide is never easily handled whether in life or in art. While Teresa Carson titles her collection for the section she demarcates as the “Elegy” portion of the manuscript, much more appears in these pages — it reads as a chronicle of how the experience of her brother’s suicide culminated in an exploration of family history. She doesn’t flinch when turning the sharp edge of her short, blunt lines upon her brother’s psychosis, her mother’s crippling depression, her father’s infidelity. Neither does she spare

herself — her own risky choices (drugs, hitchhiking, affairs) are exposed alongside her family’s failings and dysfunction.

Because she is so forthcoming, Carson makes a space with this manuscript where humanity is the prized possession: it is the thing you must admit to before proceeding. “Stop” (11), the last poem in the “Elegy” section — is a confessional where Carson whispers her relief at her brother’s death. This admission launches a reader into a world where her desire for her mother’s praise in “My Mother Said” and her pleasure at her rapist’s painful death can be gazed upon in close proximity and because it is handled so frankly, a reader can watch the story unfold without judgment, instead standing in Carson’s place as she orients you to the darkest moments and questions that have followed her all of her life.

At moments, the collection seems disorganized, but the order is definitely by design — Carson has made the collection into an echo chamber, details and themes from disparate poems bouncing off one another, adding layers of meaning at each point of contact. A string of poems near the middle of the book address sexual experiences that occurred during her adolescence and young adulthood. In “Kathy 1969” (29), Carson writes from the perspective of someone blithely confident enough get entangled with a married man who’s sleeping with her friend — and in the poem immediately following describes the experience of this same man raping her, “Dog Guards Bed” (30). The genius of the poems is that they stand on their own, but write in each other’s margins and between each other’s lines to add entirely new dimensions and remembrances to the reader’s experience.

Through her brother’s suicide, Carson is able to put a point on so many other experiences of her own that this collection ends up blurring the line between poetry and memoir — poemoir,

perhaps — in a most essential way. These poems may have been difficult to unearth in the honest and lucid way in which they are presented, but they are readily admitted and no less arresting for the effort, emerging unfaded, even after years and several lives lived, from the connective tissues where pain and memory are stored.

— Meghan Cadwallader