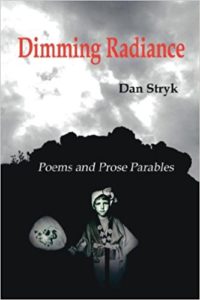

Dimming Radiance: Poems and Prose Parables

Dimming Radiance: Poems and Prose Parables,

by Dan Stryk, Wind Publications, Nicholasville, KY, 2008,

149 pages, paper, $15.00, ISBN: 978-1-893239-66-1

In a present where we are deluged with images, a world of visual and auditory white noise, where speed is of the essence and attention may only focus for a millisecond, a book like Dan Stryk’s Dimming Radiance serves as a resting place, a water lily pad on which we can slow ourselves and look carefully at the life we inhabit. Dan’s poems and parables gently demand attention to the moment we find ourselves in. As in the poem “On Viewing a Scroll by I Fu-Chiu,” where the last lines remind us softly:

An eddy

seeps from rippled pole,

surrounds us . . .

All haste,

past and future,

seems a loss. (17)

A lover of the diversity in the world and widely-traveled, Dan Stryk brings to his work influences from Japan, the Blue Ridge Mountains, France, Italy, Iran, and the shores of the muddied ponds of the Midwest. He places them in chalices of parables, tanka, brief eggshells of poems, and wide webs of spun stories. He believes that “form is strongly influenced by content,” much as Robert Creeley approached his poems, Dan feels that “form and content must find balance.” The small poem, “Snow,” unfolded before me as I sat writing this during the blizzard of a few nights ago:

Wound-covering,

the snow fell full

that day. Blending

the evening’s scattered

view, the cars

hulking our tired

street, in still

white mounds, soft-

edged. Strange

how the greatest

pain is gently shaped

by wisdom . . . (76)

I was suspended somewhere between the swirling white outside and the soft mounds of my own dreaming. It seems to me that this is what good poems do. They take us simultaneously deeper into ourselves and urge us to surrender to the whole world outside ourselves. The drifts outside my window were echoing in the drifting of the poem’s form, its regular waves.

Having read this collection, I was moved to call Dan at his home and thank him for the respite and comfort I found within these pages. What could have been a simple thanks to a fellow poet I had never met became a two and a half hour conversation about our lives, our work, and the need to stay in touch with the natural world as a source of who we are and why we write. It was clear that Dan felt great reverence and admiration for the poems of his father, Lucien, and his great friend and mentor, William Heyen. At the same time he is deeply involved with finding ways to build gates and bridges to all he observes and becomes. The poems, “Master Heron” and “Waterbird in Winter” offer a glimpse into his approach. In the first, he observes; in the latter, he is. From “Master Heron”: . . . Your samurai beak, / time after time, piercing / the ocean’s heart. (8) to the poem, “Waterbird in Winter,” where he writes . . . and then I hear / a message / murmuring through / the narrows / of my flute–like skull / as I stoop / to the small hole.” (9) To see these poems on facing pages is to take the journey with Dan from seeing to being. The epigraph fronting this poem is from a T’ang axiom: “Look as, not at, the heron to arouse the river’s spirit.”

The different forms in Dan’s poems take us from the bird-skeletal delicacy of the shorter poems to the shambling bear parables that turn the world into teaching moments. The parables are a delicious mix of used tires, world literature, jazz and country, philosophy and soggy sneakers. It is a rare gift to combine the horseshoe games of neighbors from the local meat packing plant with the Zen mindfulness of surrendering to the sunset, but Stryk calls on these varied sources to place himself and his reader in both places, trying to balance his quest for the stillness of inner peace with his need to hear “Nice one, Hun!” as he flings a dreamed-of ringer at dusk, something of clouds and iron.

This collection, as variable as it is in approach to form, holds together beautifully as a document of the continuing search of Dan Stryk to achieve balance, to be the human seeker as well as the heron he observes, peering ever deeper into the pool of the world.

I’ll leave you with a bit of “Crows in Grey Mist,”

And now — my engine softening its roar on downslope

in the valley toward Boone — I think of how we’re drawn so

deeply to the momentary. Inks pooled rich, or soft, or too

thin to observe, but felt, in flux of clarity and haze, like sud-

den flight. Things we can’t own, or love, too long . . . (20)

This review serves as only the first sip of a comforting tea, the warmth of a questioning flame at the heart’s hearth. The steam is rising now.

— Michael Macklin