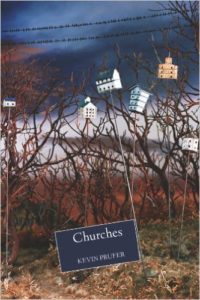

Churches

by Kevin Prufer,

by Kevin Prufer,

Four Way Books, 2014,

paper, 96 pages, $15.95,

ISBN: 978-1-935536-43-7

Buy the Book

Many of the poems in Churches, by Kevin Prufer, are full of fire, smoke, and broken glass. Their speakers often find themselves in a world figured as a womb of violence, forced to face — without the solace of religious abstraction, and often under the harshest of conditions — human mortality. Out of these wombs is born, for the reader, a necessity to contemplate the role of faith in our attempts to survive and understand the harm done to us by circumstances, or by others, but also to consider that the harms we suffer are often of our own doing. These poems frequently illustrate the failure of the coping mechanisms that we have come to rely upon in a post-Nietzschean world where religious faith is either absent, or, even worse, destructive.

The opening poem in Churches, titled “Potential Energy is Stored Energy,” highlights this question of faith. A porter lying in the snow, a victim of the explosion of a bomb planted on board a train, thinks of the infant son he and his wife had lost to fever. Neither the porter, now approaching death, nor his wife, in his memory of their son’s passing, voices the supplications a reader might expect. Rather, it is the anthropomorphized bomb that utters its prayers, ominously, to heaven, just before its stored energy is destructively released: “I give this to you, Lord, /in a wisp of smoke, in splinters /scattered in the wind and love.” These final words of the bomb are set beside the porter’s last moments in which present and past have become one, and his wife’s words to their fevered infant are now applicable also to himself: “Oh breathe, breathe, his wife was saying, /while the great unmelting snows concealed his eyes, /and up to the waiting heavens /this black plume rose.” The God of the poem is the God of bombs (and bombers) and while his heaven may be waiting, it is a heaven that admits only the smoke of wreckage.

If religious faith can no longer be of any consolation, then where do we seek solace against a harsh world? One replacement for faith, portrayed as largely ineffective and even harmful, is the numbing power of medication. The little white paper pill cup is ubiquitous throughout the book, a grail in which the speakers of the poems often seek solutions. That white cup looks bright against a backdrop of black smoke, but it is a brightness, the poems seem to argue, that obscures rather than reveals — its promise of cure seems as unreal, as unattainable as heaven. The poem titled “Paper Cup” offers the constant refrain “Here are your pills” until, in its final line, we are told: “Here are the last of your pills, little white zeros in a cup.” In a world that rains down the pain-killer Lortab like manna, there still aren’t enough pills to cure what ails us.

Churches approaches the existential problem of the death of God primarily in order to illustrate both the insufficiency of our answers and the effects of this failure. Consider the elderly speaker of “Sunday Afternoon in the Park” who, rather than being situated in the scene of the title is, instead, a mere observer, trapped within the linoleum floored world of a retirement home where the orderly’s cry of “Pills, pills, pills” leads the speaker to identify her as “the crazy woman /down the hall.” Such an institutionalized existence pales in comparison to even the quotidian world of people waiting for buses that exists outside the speaker’s window. After making some perceptive observations of the scene, the speaker wistfully, and tragically, declares,

How I love a cool Sunday morning

high above the park

after a rain.

If I could, I would jump

right through this window.

These lines are tragic largely because they illustrate real human potential, struggling, however unsuccessfully, against terms of confinement that, unlike mortality, are not necessary. We don’t have to keep the elderly drugged and shut up in homes, and the poem reminds us that this problem, among others, is man-made. It requires a God neither to blame for it, nor to solve it.

— Christopher Hornbacker