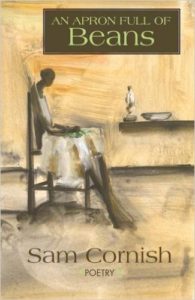

An Apron Full of Beans: New and Selected Poems

by Sam Cornish,

by Sam Cornish,

CavanKerry Press Ltd., 2008,

179 pages, paper, $16.00,

ISBN: 978–1–933880–09–9

Purchase Book

As the first Poet Laureate of the City of Boston and the author of six previous volumes of verse — in addition to his many other honors and awards — it is surprising, indeed, that Sam Cornish is occasionally omitted from the discussion of the Black Arts Movement, as his voice is just as resonant and sincere as any of his contemporaries. Thankfully, his new and selected poems An Apron Full of Beans is a splendidly comprehensive and eclectic collection, which not only affirms Cornish’s role in the American poetry of the previous century, but also demonstrates the raw force of his work today, here, in the electric pulse of now.

In his brief yet poignant introduction to this collection, Dr. James E. Smethurst argues that Cornish’s poems are remarkable for their distillation of so many period styles — particularly those of the Beats, the Black Arts Movement, and the Black Mountain School — yet remain distinct, complete, and authentic in their rhythms and sense of language. It is a point worth repeating. Cornish is just as comfortable with the short, terse lyric as he is with that wild animal called the prose poem, as we see in the collection’s moving final inclusion, “Elegy,” and it is rare that one feels the dust of age upon the older poems in the book.

Another striking quality of Cornish’s poems is the depth of craft they display page after page. There are plenty of poems here that reveal Cornish’s adept skill with necktie–skinny narratives full of plain–spoken, enjambed diction running twenty lines or fewer, such as the clipped minimalism of “Ebony:”

My father labored

in the mine his

hands blacker than

his face

face as black

as

coal his hands

darkest

coal dust

my mother

a fair skinned

woman former

schoolteacher

worked at home

read the Bible

and prayed &

I became

a Communist

But the deeper one gets inside Cornish’s universe of barbershops, broken families, and runaway slaves riding the rails of hope, we see that this style is a conscious commitment to form rather than the result of a limited range. This clearly evident in Cornish’s longer poems, such as “Woman in a Red Dress,” which shed their colloquialism and understatement for a denser, more lyrical register: “If she could count past her fingers / About her body / The words she would find / If she could read / She gathers

water / Like sounds in her head / She kneels / Like a slave / In church / Like a slave preparing / To dance . . .”

While the jacket flap for An Apron Full of Beans claims the collection is “an African–American sequel to Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass,” one wonders if such a conceptual framework is applicable or even necessary. Time and again in these poems, Sam Cornish trespasses the accepted borders between public history and private experience by evoking the voices of slaves, sharecroppers, and historical figures such as Frederick Douglass in one large cultural conversation that is self–sustaining without the added burden of arguing against Whitman’s vision of nationhood. Moreover, the questions that result about race, power, love, and loss are more relevant in this strange new century of ours as they’ve ever been. Some of the best voices in America today, such as Kevin Young, Natasha Trethewey, and A. Van Jordan are following in the footsteps of Cornish not merely because he is an indispensible African–American voice, but because he has the courage to turn his interrogative gaze upon our savage and beautiful past without casting his eyes away. Ultimately, though, An Apron Full of Beans doesn’t belong on your bookshelf as a relic of inspiration. It just belongs on your bookshelf.

— Adam Tavel