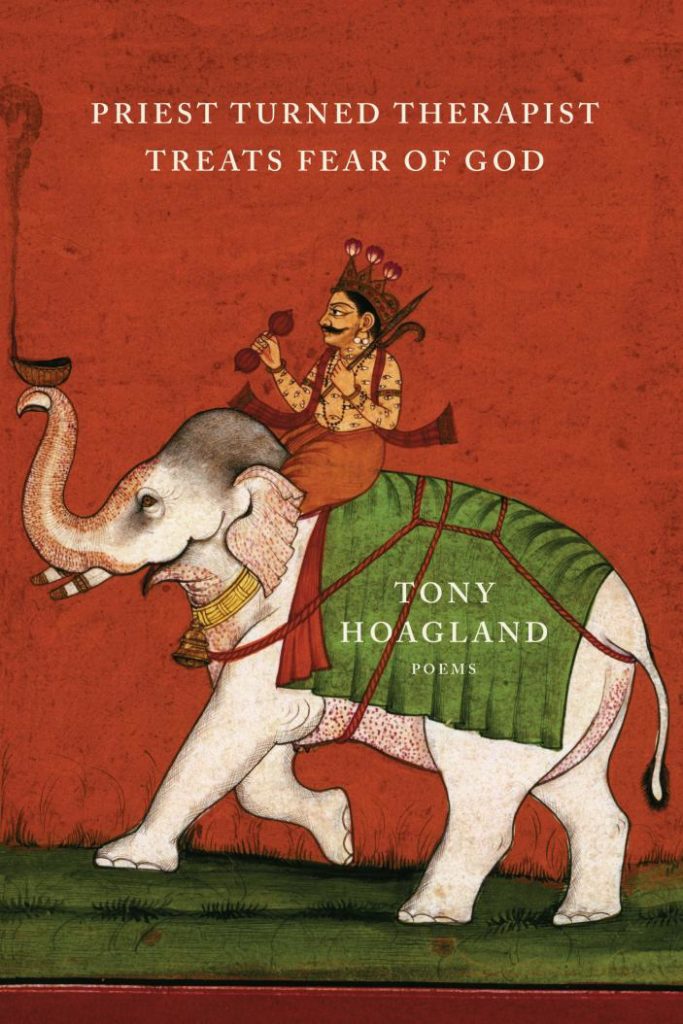

Priest Turned Therapist Treats Fear of God

Priest Turned Therapist Treats Fear of God,

by Tony Hoagland.

Graywolf, 88 pages, paper, $16.00,

ISBN: 978-5597-807-5

Tony Hoagland’s work has always been interested in hard-won wisdom. He avoids easy aesthetics or aphoristic presentments. Over Hoagland’s six previous books, we’ve come to know him as a writer of artful and cantankerous poems that challenge pervasive political, moral, and socio-economic presumptions and interrogate the sorts of beings (both self and other) that propagate and sustain such presumptions. Hoagland’s final book of poems, Priest Turned Therapist Treats Fear of God, is a sharp, graceful collection that risks sincerity and vulnerability in order to artfully elucidate the tension between the permeable individual and the ever-invading world of nature and culture.

Like his last book, Recent Changes in the Vernacular, this one opens up space for the kinds of sentiments that mean more in the face of oblivion (Hoagland died of cancer in October of 2018) than they do when sprung from naïve surety or lazy ideology. Lines about wisdom being able to “sprout honesties / like flowers” are saccharine and difficult to pull off, but nestled in the larger context of his tempered, unapologetic style, they work The same poem, “Achilles,” notes that “we / already have chosen the strange / garments of confusion / we will die in” and that we “love / the thrill of enemies” and “. . . burn / through beauty like it was / wrapping paper.”

A sense that oblivion is close at hand pervades the book. Poems like “In the Waiting Room with Leonard Cohen” and “Achilles” are borne out in hospital gloom, cancer and its accompanying fatigues close at hand. But Hoagland stays sharp and doesn’t acquiesce to the tropes of illness. The latter poem eulogizes the plight of a patient in the hospital bay across from Hoagland: “Achilles is being carried from the field. / Three-fourths covered by a thin green gown; one / big bare shoulder sticking out.” A kind of piteous nobility carries the poem. After Achilles is wheeled into radiology, the poem concludes,“And then I am here alone / the one to weep / and it is myself I weep for.” By drawing a line between the epics of classical antiquity and the heavy succumbing of the individual to bodily plague and extinction, Hoagland reveals his high regard for the human drama; the bearing out of fate, whether it is personal, literary, or national, makes no difference. It is all the same beautiful and confounding trouble.

Other poems like “Couture” and “An Ordinary Night in Athens Ohio” are simply a seasoned poet with a good ear working well. The latter poem’s first several couplets skip briskly, a little drunk on sound, and risk going too far:

Those children in pajamas

in the big suburban houses

are not dreaming

of fireflies in jars

nor model cars,

but of fist-fighting

on Mars

in bodies not their own. . . .

The poem settles, and takes us into the kinds of wholesome quandaries of a collectively idealized past: “they are not feeding the hamster / small bits of lettuce / and changing its name / from Joe to Josephine, and back” before diving back in, “but sprinting over the rooftops / of burning Dairy Queens / and aiming shoulder-launched rockets / into shopping malls.” It’s a metaphysical requiem for a lost, albeit somewhat imagined, simplicity. It mourns not the supposed virtues of an American past, but the broader abandonment of nostalgia and the embrace of a violent, fiery future.

Priest Turns Therapist Treats Fear of God is a testament to the tenacity of Hoagland’s poetics. Illness serves to refine and clarify his vision and stretch out his big heart. This volume is at once tender and well honed. Reading it, one feels as though they’re encountering a poet vindicated by the vicissitudes of time — not exactly comfortable, but somewhat comfortable with discomfort. As I reflect on the fragile legacy of any poet, another line from “Achilles” comes to mind: “Look, don’t pity him! His imagination is not dead!” We would do well to look to Hoagland’s poems and to read and reread them. They are the record of a keen, funny, self-deprecating, imaginative, and sometimes controversial poet. Now it is up to us to see that his work endures beyond the moment.

— Luc Diggle