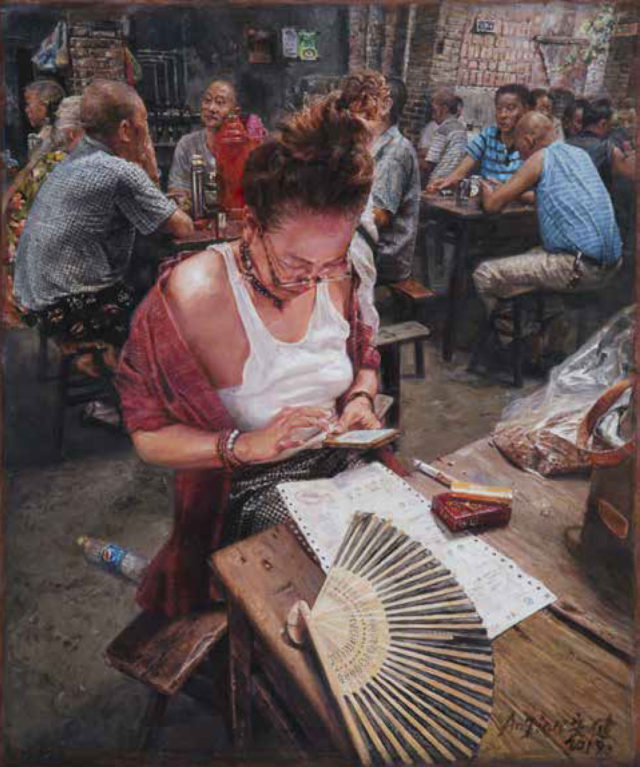

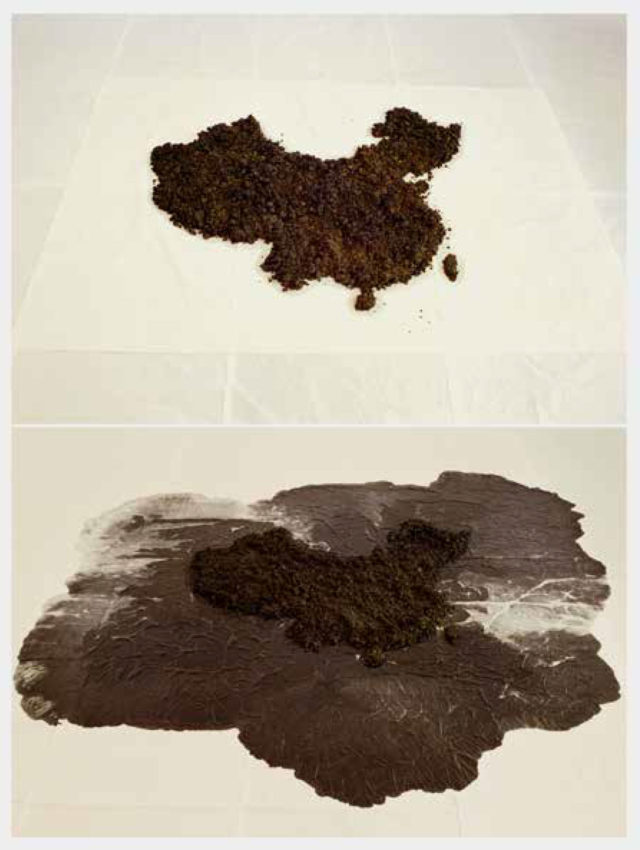

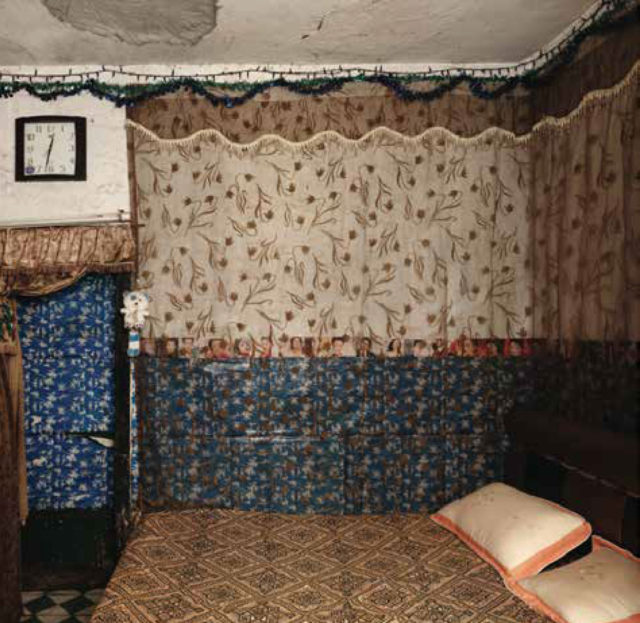

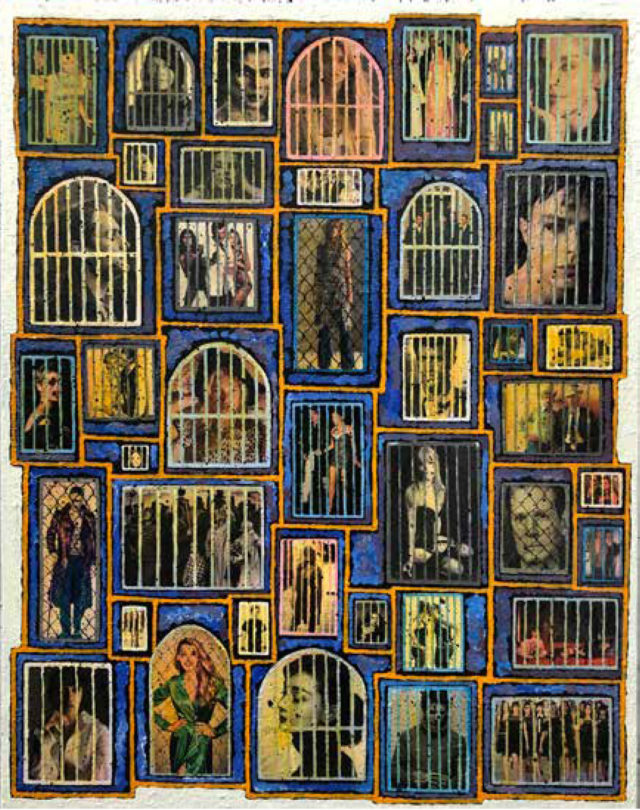

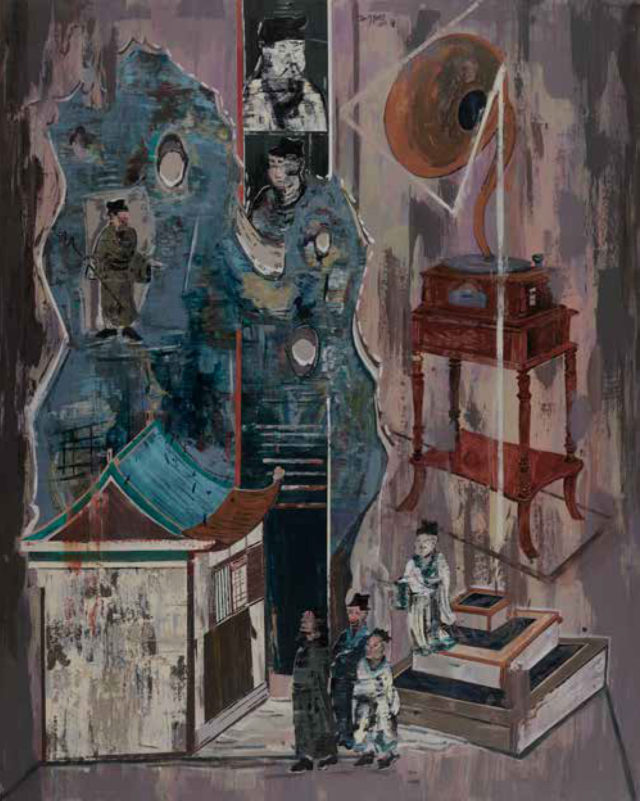

Our latest Fall 2021 Issue of The Café Review continues our mission to bring Maine poetry to the world and poetry from around the world to Maine with our special Chinese issue featuring poetry by Akuwuwu, Qimanqul Awut, Chi Le Chuan, Hei Feng, Liu Hongli, Bai Hua, Gao Jiangang, Jimu Langge, Yang Li, Hu Liang, Hou Ma, Liang Ping, Wang Ping, Han Qing, Yi Sha, Li Wanfeng, An Wanmei, Wu Xiangyang, He Xiaozhu, Yuan Xin, Gong Xuemin, Xiong Yan, Yu Yan, Ning Yaoyu, Na Ye, Xiang Yixian, Xi Yongjun, Zhai Yongming, Yu Yoyo, Li Yuansheng, Li Yun and He Zhong, translated by Sophia Kidd, Chen Xiaoyuan, Wang Ping and Fan Jinghua. Also featuring artwork by Chen Anjian, Tang Changhu, Yang Chunsheng, Zhu Gang, Dai Guangyu, Wang Haichuan, Hu Jiayi, Wang Jun, He Liping, Chen Weimin, He Yang, Zeng Yang, Wang Yanxin and Su Zhengxun.

As always, we are an all volunteer micro-pub producing printed publications quarterly from Portland, Maine. If you love our issues and work here online, support us by donating or subscribing. Without our subscribers, we would not exist!

Introduction by Guest Editor, Sophia Kidd

Being on the ground here in China for decades, I see multiple histories of Chinese art and poetry within China, and additional ones outside of China. The ones outside China tend to be disconnected from ones inside China. I have been banging my head against this wall, between inner and outer, for years. It then occurred to me that some of the narratives on Chinese art and poetry could have been better served if they had enlisted varying points of view. Thus, I invited four contributing editors: Liang Ping, the Chairman of the Sichuan Literary and Arts Federation; Xi Yongjun, the peoples’ editor; YuYoyo, one of China’s youngest and most exciting voices of poetry; and Wang Ping, who has lived and taught for decades in the United States. While Liang, Xi, Yu, and I have focused upon Chongqing and Chengdu poetry as representative of China’s Southwest BaShu poetry tradition; Wang Ping’s editorial contributions have expanded this issue’s focus out onto the periphery of China’s poetic imagination, into the highlands of Tibet and the hinterlands of Xinjiang and Mongolia. Wang Ping’s contribution also courses along the arterial waterways of China, along the Yellow and Yangtze Rivers, skirting mythopoetic metropolises and emptying out into the Pacific Ocean.

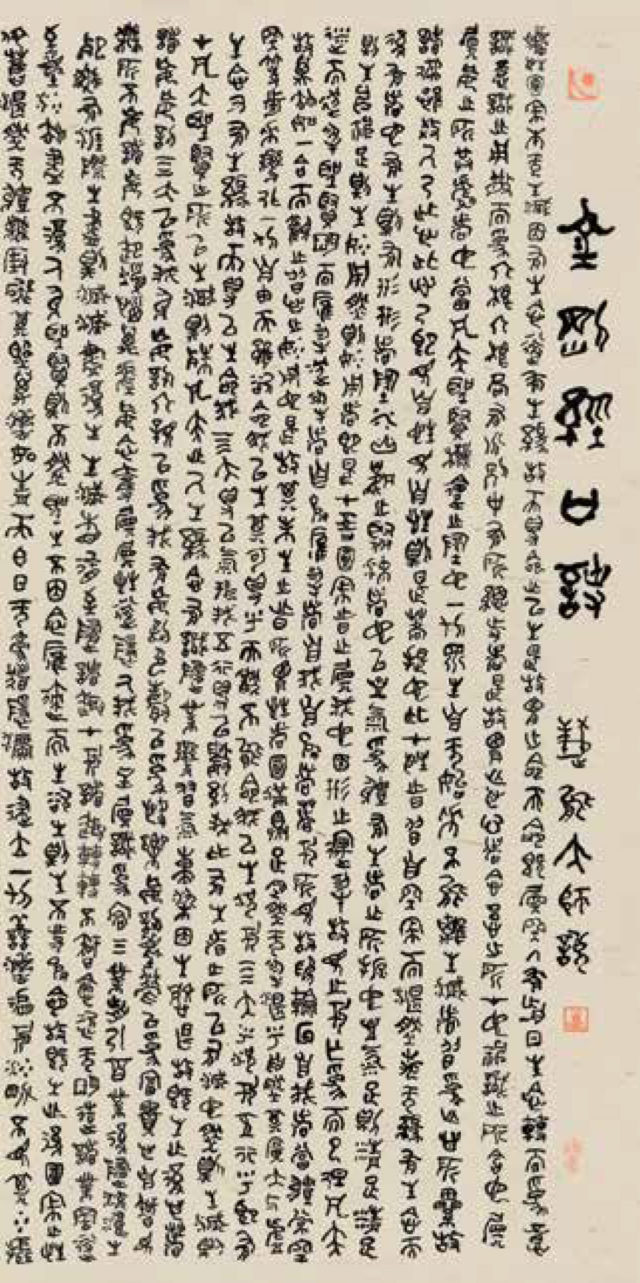

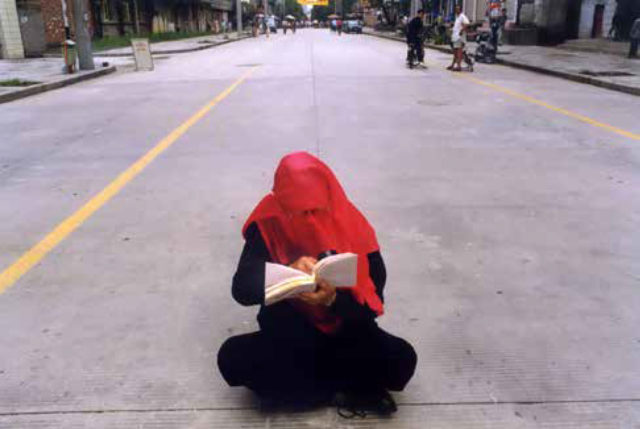

For the artworks in this issue, I decided once again that more than one cook would make the best soup. I invited five curators of contemporary Chinese art with a reputation for selecting relevant and vital artists for museums and galleries throughout China right now. They were asked to select representative Chengdu and Chongqing artists, either working and creating here now, or having been born and raised here. Liao Liao Arts Dissemination Institute provides this issue with some of its most professional and elegant artworks. Ni Kun and Tian Meng provide us with artworks by some of the most experimental and groundbreaking artists of Southwest China’s avant-garde, while Cui Fuli represents a young and emerging curator’s vantage point. Xi Yongjun provides us with selections of classical artforms, with the traditional inkwash and calligraphic works. I added one artist to this roster, Zhu Gang, who, although he is a member of the 1990s avant-garde and has been producing since then; he is so averse to institutions either political or commercial, that part of his practice is to refrain from exhibiting or selling it, trusting me to share it with audiences abroad. Thus we see the fallibility of gatekeeping, and of wallbuilding. For there are elements in life which will not be kept in by walls, and there are moments of genius which fail to be cultivated by those we trust to bring real beauty, truth, and goodness to light for us.

China is indeed changing. This is no longer just Allen Ginsberg or Gary Snyder’s China. It’s not just the land of the laughing Buddha or the Daoist sage. It is also the land of fintech and contact tracing, of the world’s tallest buildings and largest airports, of artists and poets who embed and encode their dreams and anguish in metaphor and rhetorical structure that would make Lorca and Borges drool. This is the cultural ethos of the Three Teachings, of Buddhism, Daoism, and above all, Confucianism, with its careful rituals meant to invoke the paradigmatic magical sovereignty of the kings of Zhou, three thousand years ago. I know, this is a lot for some dozens of poems and art works to convey to you, but they are powerful, and I trust they will do their job.

I want to thank Thexis Foundation and Sichuan University for supporting me in this endeavor. I want to thank all the contributing editors, curators, and translators for their painstaking work and devotion their craft, and their selflessness in giving to this issue. Thank you to Steve for his trust in me, and to his huge crew of volunteers for all that they do in bringing The Café Review to readers for the past 30 years. Much gratitude, as well, to you, our reader, for reading these poems, rolling your eyes across these images, and for being open to what China has to offer today, in these tense times between our great nations.

— Sophia Kidd, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China, 9.10.21