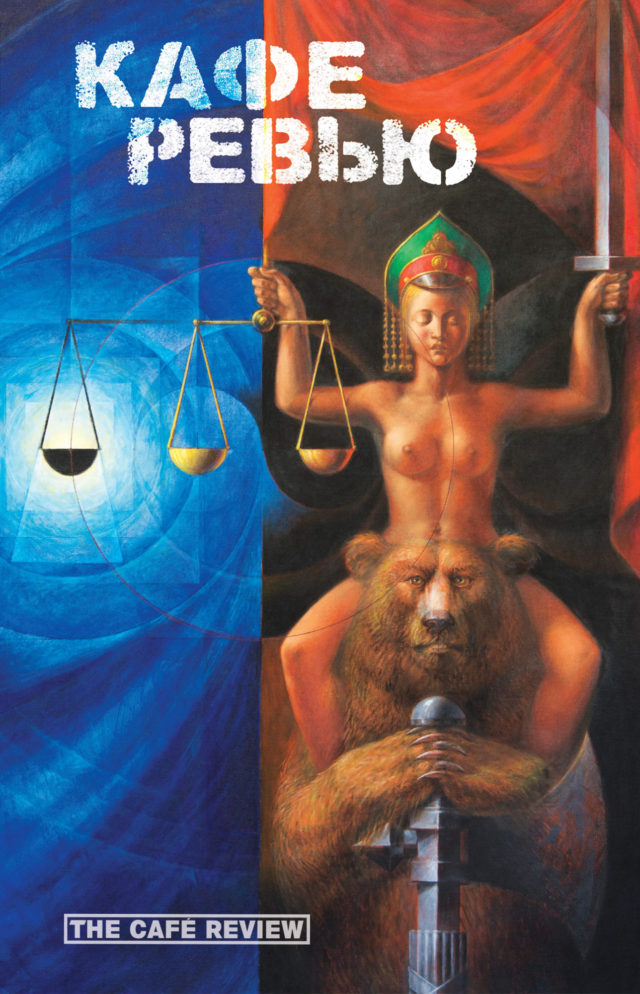

Café Review 2018 Summer Icelandic Issue

Our latest Summer 2018 Issue of The Café Review is a special issue centering around Icelandic poetry featuring poetry by Soffía Bjarnadóttir, Ragnheiður Erla Björnsdóttir, Vilborg Dagbjartsdóttir, Kristín Eiriksdóttir, Gyrðir Elíasson, Sigurlín Bjarney Gísladóttir, Einar Már Guðmundsson, Ingibjörg Háraldsdóttir, Ísak Harðarson, Þorvaldur Sigurbjörn Helgason, Dagur Hjartarson, Fríða Ísberg, Anton Helgi Jónsson, Elías Knörr, Gerður Kristný, Ingunn Lára, Hlín Leifsdóttir, Jón Örn Loðmfjörð (Lommi), Bragi Ólafsson, Ragnar Helgi Ólafsson, Kristín Ómarsdóttir, Óskar Árni Óskarsson, Sigurður Pálsson, Kött Grá Pje, Aðalsteinn Ásberg Sigurðsson, Magnús Sigurðsson, Sjón, Ingunn Snædal, Kristín Svava Tómasdóttir, Kári Tulinius, Linda Vilhjálmsdóttir, Hrafnhildur Þórhallsdóttir, and Sigurbjörg Þrástardóttir. Translations were possible thanks to the hard work of Áslaug Agnarsdöttir, Larissa Kyzer, Sigurður A. Magnússon, Bernard Scudder, Lytton Smith, K. B. Thors, Anna Yates, and Meg Matich. This issue features work by artists Michelle Bird, Elín Elísabet Einarsdóttir, Ragnar Jónsson and Helga Thorodssen. Special thanks to guest editors Meg Matich and Magnús Sigurðsson for making all of this possible.

As always, we are an all volunteer micro-pub producing printed publications quarterly from Portland, Maine. If you love our issues and work here online, support us by donating or subscribing. Without our subscribers, we would not exist!

Issue Introduction

The first poem that I learned as a child was said to have been contrived by an elf woman. I heard it from my mother, who never tired of telling me stories of the hidden world of the elves:

Ló, ló, mín Lappa,

sára ber þú tappa,

það veldur því, að konurnar

kunna þér ekki að klappa.

According to the story, Lappa was an elven-cow that appeared suddenly in the world of human beings. It was locked in a stall in a cowshed. In the human world, she became difficult to milk, but one evening, a voice outside of the barn window recited a poem of sorts to the cow. The creature, or creatures, that recited the verse then stroked the cow and called her by her name. After that, she became very easy to milk.

Poetry has been written in Iceland since its settlement over 1,000 years ago. Some say that Icelanders have, from the very beginning, had a proclivity for literary creation. In the sagas of the Icelanders, we’re sometimes told of poets who sailed to other countries and recited poetry for the king in exchange for payment. In these stories, it’s almost as if the same language was used in all countries across Northern Europe, and that everyone understood everyone else. In the present, on festive occasions, it’s sometimes asserted that modern Icelanders nonchalantly and happily read the old sagas and have no difficulty whatsoever understanding them.

That’s an exaggeration. Most modern Icelanders can only read the sagas of our ancestors in special editions with updated spelling and grammatical conventions, and “dróttkvæði” — ancient Iceland’s highly stylized verses — are even less understandable. This also seems to have been the reality in our national past. When we dive into the histories of our poets, it’s clear that foreign kings didn’t necessarily or consistently understand the Icelanders’ poetic creations and even paid them to refrain from reciting — just as often as to recite — their poems.

Modern Icelanders want to believe that they understand the old poets. It reminds me of a belief in elves. Throughout the ages, folk belief has transmitted the notion that beings — very similar to human beings — reside in Iceland’s hillocks and hillsides. Those are the hidden people, the elves. In reality, nobody believes in the hidden world anymore, but nobody wants to deny their existence either. There’s a certain temptation to believing in fictional worlds.

Icelanders also believe that not only the kings, but also the people of foreign lands wanted to listen to them and could, in point of fact, understand them. These days, poets and authors travel around the globe with their creations. Authors that write crime novels full of twists and turns draw the most attention, and are, in that way, alike the authors of the old Icelandic sagas — but a certain number of poets have also seen their work travel the world.

Which raises the question: is there something idiosyncratic about Icelandic poetry? What characterizes Icelandic poets?