Big Little City

Big Little City, by Mike Bove,

Moon Pie Press, 2018,

71 pages, paper, $15.00,

ISBN: 9781732362420

Mike Bove’s Big Little City offers a heartfelt and detailed portrait of Portland, Maine, the author’s city of origin. The speaker of these detailed poems excavates personal memory and history as he struggles to chart his own path. Bove’s repeated map-making metaphor and his contemplative diction help create the sense of exploration — a meditative walk through the city he loves.

Each of the four sections opens with a short poem titled “Cartography in Retrospect,” marking four steps in the narrator’s coming of age. In the first cartography poem, the speaker uses his “father’s cracked map to walk a line” but gets lost when a marsh comes up in the dark. He curses his father, but continues on his difficult way. Bove’s ruminative style is evident in this first poem: “I can think of several wrong ways to draw a map. / All it takes is one slack stride for regret (bitter muse) / to set down coordinates with pinprick precision.”

In “Cartography in Retrospect II” the narrator wonders how he ended up “so far from self.” He has to learn the legend “and learn it again.” In “Cartography in Retrospect III” he must make his own map, and finally, in “Cartography in Retrospect IV” the speaker has so mastered his direction, he no longer needs the map he learned to draw. Instead, he watches the stars and “counts out paces.” In the end he comes home to “take up my pen and put it all down.”

As he continues to find his way, the speaker of these poems weaves present experience with excavated bits of the past. He contemplates the history of “The Old City Landfill,” soon to become a solar farm, as just another “sum / in the equation of layered land.” He also digs into the soil of Deering Oaks Park, superimposing the 2018 farmer’s market on the “dirt-red crimson” battlefield of 1689 (“Farmer’s Market”).

Bove’s layered phrases and lush verbal constructions suggest his contemplation of the city’s archeology, as in his remarkably titled poem “There is a Rumor That During Construction of one of Portland’s Prominent Thoroughfares in the 1850s, Some Workers Died in a Freak Accident and the Road was Built Atop Their Bodies.” As the workers weave “in and out,” so do the phrases of this sentence:

some nights I lie awake

and think about those men, imagine them

sitting up to wipe their eyes and climb, glowing,

out of the muck to stalk the street they almost built,

weaving in and out of hotels.

That these long-ago builders remain a part of the modern city, just as the 1689 battle still exists in the bedrock of Deering Oaks Park, is part of the central theme of Big Little City.

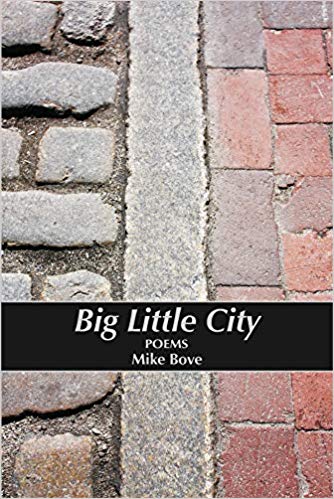

The book’s title poem concludes the collection, bringing the narrator home to become a literal part of the city he loves, thus accomplishing the goal set out in his cartography poems. He sees himself “lodged / between the stones . . . / so many small pieces . . . to collect and build / a new me.” His grandfather’s name “hangs in the church downtown” and his father’s “gauzy footprints appear in the cobblestones / he spirited away from Bramhall Street.” Even the unusual cover photo — an extreme close-up of a Portland street taken by the author’s son — suggests the close relationship of the narrator to the physical city. Anyone who has witnessed street work done on intown Portland thoroughfares has seen the careful layering of gravel and sand to stabilize the bricks or cobblestones. This is an apt metaphor for Bove’s meditative explorations.

— Jeri Theriault